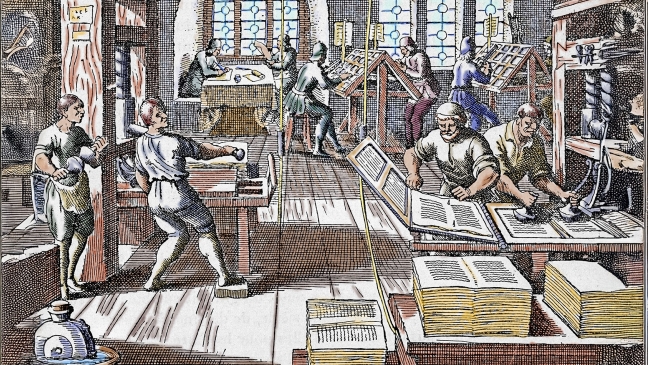

One of my favourite novels, Umberto EcoŌĆÖs FoucaultŌĆÖs Pendulum, features a fictional vanity-publishing house, run by a character called Mr Garamond.

Garamond convinces aspiring authors that their manuscripts are worthy of publication, even if they have to pay for it themselves, through creating an aura of exclusivity and importance around his press.

He makes writers feel they are part of a select group, tapping into their vanity and their need to be recognised - and, in the process, ensures a steady stream of manuscripts and revenue for the publishing house.

I was recently reminded of this book because it has begun to feel, to me at least, that this is how academia works today. In our eagerness for recognition, we write as much as we can: article after article in every journal going.

It is virtually impossible to keep up with everything being published in a given field, but any suggestion that we emphasise quality over quantity risks being seen as a call to ŌĆ£slow downŌĆØ science.

Meanwhile, we volunteer to peer review everything for free, while publishers make record profits.

This eagerness to be recognised is not exclusive to academia, though. It is a very human need thatŌĆÖs also exhibited in the world of educational book publishing.

Education books covering the same ground

DonŌĆÖt get me wrong, there are a lot of educationalists, teachers and other experts who have plenty of worthwhile ideas to communicate. But I find it increasingly hard to keep up with all the books being published.

It strikes me that, just like in academia, it might be best if we - dare I say it? - slow down a little.

When IŌĆÖve said this in the past, people have pointed out that if even one person takes something useful away from a publication, that makes it worthwhile.

But, unlike journal articles, many of which are accessible to anyone - through open access and pre-print publications - so-called ŌĆ£edubooksŌĆØ are generally not freely available, nor are they peer-reviewed as standard.

While education practitioners can easily comment on research (which is a good thing), it is much harder for researchers to comment on edubooks. I, for one, wonŌĆÖt be buying every book that gets published, especially when I know little about its contents.

All of this means that there is a lack of transparency in the system, and so we should be wary of how reliable the information in some of these books might be.

Some might feel that I am being overly critical here, but my impression is that there are a lot of books covering very similar ground. The market appears to be flooded with slightly different takes on the same popular themes: direct instruction, retrieval practice, cognitive load or criticism of discovery learning.

IŌĆÖm not sure how useful this is. There is a risk that it encourages teachers and school leaders to restrict themselves to reading about a narrow set of educational topics.

We also have to remember the importance of tracing ideas and references from their source to academic claims. This is becoming harder and harder with more closed sources and self-referencing.

Ultimately, then, reading a slew of edubooks might actually undermine efforts to make yourself and your school truly evidence-informed.

In addition, while I completely understand the eagerness to communicate your ideas, maybe - as in academia - we need to recognise that educational publishing is just producing too much. The book publishers donŌĆÖt mind. But perhaps those of us working in education should.

Christian Bokhove is a professor in mathematics education at the University of Southampton and a specialist in research methodologies

For an indispensable look at the weekŌĆÖs biggest stories and talking points, sign up for our Weekly Debrief newsletter