MATs ŌĆśneed guidanceŌĆÖ on investments as returns soar

Multi-academy trusts need more guidance on how to safely invest their surpluses, experts warn, as figures show that many are tripling their returns.

Increasingly, trusts are depositing their extra cash through online platforms that allow them to use multiple savings accounts and get better interest returns.

But while some MATs made millions through investing their funds last year, there are fears that others are missing out entirely, particularly smaller trusts.

Experts also warn that, as the practice spreads, more guidance is needed on the acceptable level of investment risk for trusts.

The Department for Education has said it is engaging with the sector and financial institutions to help raise awareness of how schools can earn more from their money.

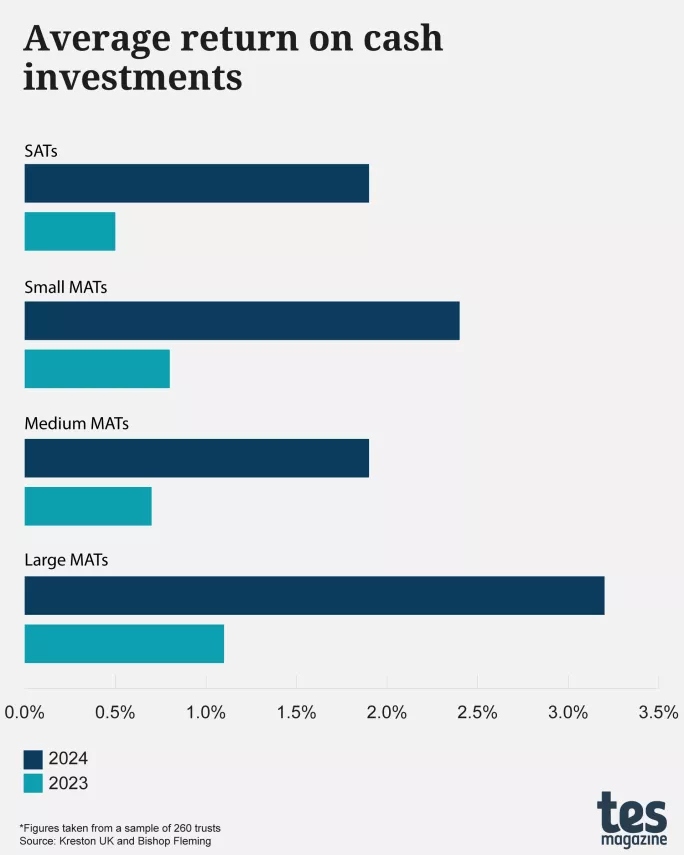

Analysis shared with Tes by accountants Bishop Fleming shows that large MATs made an average 3.2 per cent return on their cash investments last year.

MATsŌĆÖ ŌĆśsharp riseŌĆÖ in investment returns

The average for both single-academy trusts (SATs) and medium-sized MATs was 1.9 per cent.

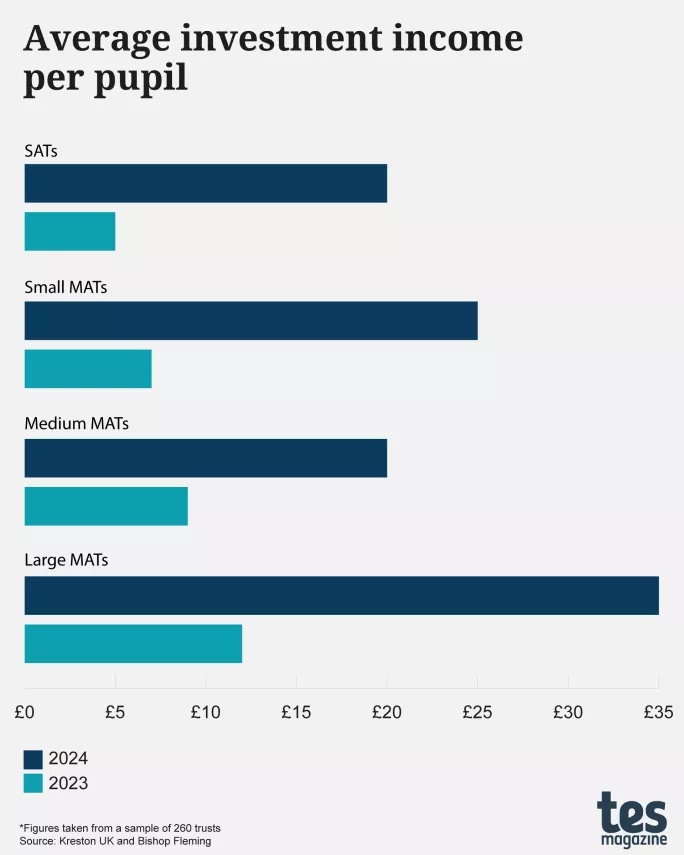

And a ŌĆ£sharp rise in returnsŌĆØ resulted in large MATs, with more than 7,500 pupils, making an average of ┬Ż35 per pupil in investment income last year, according to a report by Kreston UK.

Again, the corresponding figures for SATs and medium-sized MATs were lower, with both having an average return from investments of ┬Ż20 per pupil during 2023-24.

The amounts raised ŌĆ£can be enough to fund a capital projectŌĆØ, said Kevin Connor, head of academies at Bishop Fleming.

╠²

And with school funding increasingly squeezed, trusts are keen to look at new ways to make their cash go further.

For some, this resulted in big successes last year as interest rates climbed above 5 per cent.

For example, EnglandŌĆÖs biggest MAT, United Learning Trust, made ┬Ż270,000 in investment income and ┬Ż5.3 million in bank interest in 2023-24 - up from ┬Ż1.9 million the year before. A spokesperson said the trust would be happy to provide advice to others looking at their options.

As previously reported by Tes, Northern Education Trust was able to make ┬Ż1.2 million from credit sweeping.

Oasis Community Learning, meanwhile, reported ┬Ż3.3 million from short-term deposits, up from ┬Ż2.2 million the year before.

John Barneby, chief executive of Oasis, said getting good returns ŌĆ£takes timeŌĆØ and involves having people to monitor interest rates and move money around.

ŌĆ£YouŌĆÖve got to have very tight controls and very good forecasts for cash flow to allow you to do this,ŌĆØ he said.

The Kemnal Academies Trust, which runs 45 schools, has also been making investments after getting independent advice, its 2023-24 accounts state.

But not all trusts are investing. Nigel Brunning, chief operating officer at South East Essex Academy Trust (SEEAT), which has eight schools, said: ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs a real mixed bag. Some trusts are doing really, really well and some trusts almost arenŌĆÖt bothering.ŌĆØ

The average return across the 260 trusts surveyed by Kreston UK was ┬Ż113,000, its Academies Benchmarking Report shows.

- MAT funding: Academy trusts in deficit triple in three years

- Trust finances: MAT makes ┬Ż1.2 million from ŌĆścredit sweepingŌĆÖ

- MAT strategy: Has your trust got its strategy right?

The average returns have increased since 2023, when medium-sized MATs saw 0.7 per cent and large MATs 1.1 per cent.

But across all trust types, 2024 brought stronger returns: large MATs nearly tripled their average investment income per pupil from ┬Ż12 in 2023 to ┬Ż35, and SATs saw average investment income per pupil quadruple from ┬Ż5 to ┬Ż20.

╠²

Last year Mr Brunning found that in investment income during 2022-23. He estimated at the time that this could increase to ┬Ż100 million for 2023-24.

He said there is ŌĆ£no excuseŌĆØ not to invest for larger trusts, which he said should be able to employ a specialist treasury manager if they do not have the capacity to do it with existing staff.

ŌĆ£CEOs and trustees should be setting targets for their finance teams on this,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£And trustees should be holding their accounting officers to account on it.ŌĆØ

SEEAT was able to earn ┬Ż202,000 from ┬Ż4.6 million in cash balances last year, which Mr Brunning said meant it had more money to spend across the trustŌĆÖs eight schools.

One of the financial strategies that it used was a shorter-term deposit in an account with Nationwide that paid 3.6 per cent interest. The trust would transfer cash into the account at the start of the month and then move it back to a current account at the end of the month before wages came out.

A DfE spokesperson said: ŌĆ£We provide guidance to trusts on how to manage their investments within the Academy Trust Handbook and we encourage all schools to speak to their current or alternative banks to understand if banking efficiencies can be made and more suitable products are available to them.ŌĆØ

Trusts are allowed to invest, as set out in the , but must ensure that ŌĆ£security of funds takes precedence over revenue maximisationŌĆØ - basically, trusts should not risk their cash.

They must have an investment policy to manage cash management activities, the handbook states.

Writing for Tes last year, Tom Campbell, chief executive of E-ACT multi-academy trust, outlined how some trusts and local authorities had opted to invest their reserves in financial markets for higher returns, with approval from the Education and Skills Funding Agency - but not all trust boards had the confidence or expertise to do this.

He suggested that the trust sector could pool its reserves for investment, and estimated that, if the sector pooled around ┬Ż6 billion in reserves, this could potentially yield around ┬Ż600 million in income per year.

Simon Oxenham, chief operating officer at Woodard Academies, which has six schools in the South East, North East and West Midlands, said he agreed that the Department for Education could potentially invest reserves collectively for bigger returns.

He said that trusts need to weigh up the time they dedicate to making investments against the returns. ŌĆ£It would be sensible for the DfE to put out some guidance on investing reserves,ŌĆØ he said.

Meanwhile, Phil Beecher, chief finance officer at Active Learning Trust, explained that the trust╠²is now moving╠²ŌĆ£the majorityŌĆØ of its cash balances to money market funds that he described as low-risk investments╠²in╠²short-term corporate╠²and government╠²debts which generate more income╠²with an expected return of 4.98 per cent.╠²Last year they generated╠²┬Ż543,000 with an effective interest rate of 3.86 per cent from normal interest-bearing accounts.

Call for guidance on ŌĆśacceptable riskŌĆÖ

Education banking consultant Ian Buss said: ŌĆ£The disappointing thing is that not every trust does this.

ŌĆ£You will sometimes find a trustee that is very stuck in their ways and is a barrier, and thatŌĆÖs generally caused by a lack of understanding.ŌĆØ

Interest rates had been very low before 2022, Mr Buss highlighted in a Confederation of School Trusts (CST) workshop for trust finance professionals last week, meaning that there was not much incentive for trusts to think about their investments policies.

However, understanding how to make a good return without risk can be more difficult for some trusts - especially those with much smaller finance teams.

Sam Henson, deputy chief executive of the National Governance Association, said there was still variation in practice across trust boards, which play a key role in setting parameters for reserves policies and holding leaders accountable for financial decisions.

ŌĆ£Many boards navigate this well, but clearer guidance on acceptable risk levels and expected rates of return could provide a valuable benchmark, helping boards enhance their oversight and maximise the impact of their financial stewardship,ŌĆØ he added.

Benedicte Yue, chief financial officer at River Learning Trust, agreed that more guidance would be helpful.

She told Tes: ŌĆ£Whilst the risk of UK-regulated bank failure has reduced since the financial crisis with strengthened oversight and capital requirements, trusts should exercise reasonable care in investing their surplus cash, paying particular attention to their liquidity needs and to the type of investments.

ŌĆ£Anything where the capital is at risk or unethical could be considered contentious and could require DfE approval. Further guidance in this area may be helpful.ŌĆØ

Leora Cruddas, chief executive of the CST, said the organisation would consider looking into trustsŌĆÖ successes in increasing investment income to see if there were lessons for the wider sector.

Simon Newitt, chief financial officer at Lift Schools, said his trust was able to make ┬Ż2.5 million in 2023-24 through investing in interest-bearing accounts and deposits managed using the Insignis platform. He added that 22 of 57 Lift schools had less general annual grant income than the interest the trust secured through its strategy.

ŌĆ£As a large trust, we were able to maximise returns in this way, but clearly this may be more challenging for smaller trusts or for SATs,ŌĆØ Mr Newitt said.

He added that it would be beneficial for trusts to work collectively in this area.

Barriers to investment

Mr Buss said common barriers for trusts preventing them from using multiple banks to maximise returns on their surplus cash include: the length of time it takes to open a new account, trustees being risk-averse, fears that the trust may need cash quickly and concerns about the time needed to monitor multiple deposits.

One trust finance lead attending CSTŌĆÖs workshop on investments said it can take ŌĆ£weeks, if not monthsŌĆØ to set up a new account.

ŌĆ£The larger trusts have the larger finance teams and people in those CFO-type roles who are really charged with making sure theyŌĆÖre generating these sorts of incomes and identifying these opportunities,ŌĆØ said Mr Connor.

ŌĆ£Some of those smaller trusts and SATs likely donŌĆÖt have those.ŌĆØ

The news of some trustsŌĆÖ investment success comes amid a difficult financial landscape for schools. The proportion of trusts reporting in-year deficits tripled between 2021 and 2024, and many have warned that funding announced for 2025-26 will leave them having to make cuts.

Mark Blackman, director of education consultancy Leadership Together, previously said trust leaders were having to become ŌĆ£ever more creative to maximise the income to support the day-to-day experience of childrenŌĆØ.

For trusts with smaller cash balances, making significant investment income is harder, but Mr Buss said there are still things they can do.

ŌĆ£If a trust is in a position where its cash is so tight at the end of the month that itŌĆÖs almost down to zero, obviously longer-term deposits are something they canŌĆÖt do,ŌĆØ he explained.

ŌĆ£But they might be able to look at very short-term deposits to earn a little bit more interest for a few weeks until they have to take it out to pay wages at the end of the month.ŌĆØ

He said that around nine in 10 trusts needed to create an investment policy or update theirs.

However, while experts recommend that all trusts look at their options, Mr Brunning warned that interest rates are now going down.

ŌĆ£Last year was the bumper year to make some money,ŌĆØ he said.

ŌĆ£Every trust that has a positive month-end balance should at least explore what the opportunities are, and look at getting some sort of professional advice,ŌĆØ Mr Buss added.

The DfE has been contacted for comment.

Find our interactive map of EnglandŌĆÖs multi-academy trusts by clicking here, where you will also find links to all of our MAT Tracker content

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article