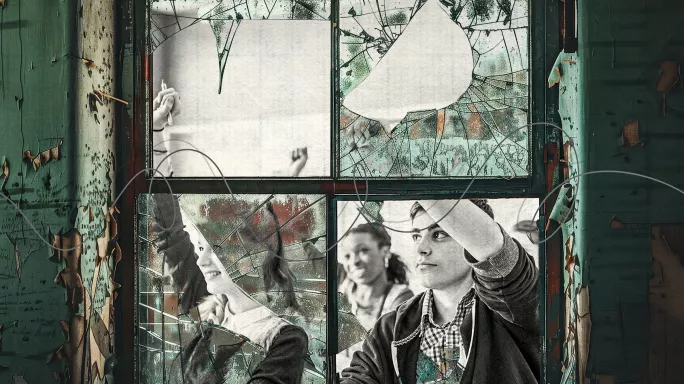

ŌĆśOur site is on a knife edgeŌĆÖ: the school buildings crisis deepens

ŌĆ£Our site is on a knife edge,ŌĆØ says Julia Polley, headteacher at The Wensleydale School, a maintained secondary in Leyburn, North Yorkshire.

ŌĆ£The number of times IŌĆÖve held up bits of piping with scaffold... WeŌĆÖve got boilers that have been condemned. WeŌĆÖve got windows with original metal frames that are buckling and fracturing...ŌĆØ

The list goes on. ŌĆ£In the school kitchen weŌĆÖve got flaking paint, which needs to be completely stripped and redone. WeŌĆÖve got cookers that really need replacing.ŌĆØ

Polley is aware that there are health and safety concerns. ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm worried,ŌĆØ she tells Tes. But, she adds, the school canŌĆÖt afford to solve these issues, and the local authority isnŌĆÖt forthcoming with funding for buildings maintenance either. ŌĆ£They say, ŌĆśUnless it goes kaboom, thereŌĆÖs no money.ŌĆÖŌĆØ

Problems with school buildings

The issue of underinvestment in schools has been discussed for years - but it is examples like these that underline just how pressing it is now becoming.

WhatŌĆÖs more, despite seemingly good news in the June Spending Review, in which the government confirmed an extra ┬Ż4.7 billion for schools, experts noted that the settlement is ŌĆ£tightŌĆØ because it amounts to a real-terms fall in budgets.

Increases to the minimum wage and employer national insurance contributions have pushed up costs in areas such as cleaning and catering, severely impacting schools. And what capital funding is available for repairs is reaching fewer and fewer settings each year.

All this means that schools are facing dangerous situations on their sites - with few obvious solutions. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs desperate,ŌĆØ says Kate Chisholm, executive headteacher at Oakfield Junior and Infant schools and Wyndham Primary, part of Smart multi-academy trust in Newcastle.

Like Polley, Chisholm can list countless maintenance problems across her schools.

ŌĆ£We had a fire because the heaters were as old as the buildings, which are 60 years old, and they set the floor on fire,ŌĆØ she recalls. ŌĆ£We have a building that is like a greenhouse - freezing in winter and boiling in summer.ŌĆØ A few years ago the temperature in there reached 53C, she says.

Robust risk assessments

Chisholm has even had problems with safety features. ŌĆ£We had to close a fire escape off because it is rusted and we canŌĆÖt afford to replace the barriers,ŌĆØ she says.

For each of these issues, her team has found a workaround. ŌĆ£Our children are safe when theyŌĆÖre in school,ŌĆØ Chisholm says. ŌĆ£We have a very robust risk assessment in place.ŌĆØ

But to make that possible, something has to give. ŌĆ£In two of my schools, we have to budget ┬Ż100,000 every year just to keep the buildings safe. That could be spent on teaching and learning,ŌĆØ she explains.

The trust has sought capital funding, Chisholm says, but has been rejected twice, having been told that ŌĆ£the school wasnŌĆÖt bad enough to get new buildingsŌĆØ.

So, how bad do conditions have to get for funding to become available?

For Polley in Yorkshire, it took a legionella scare for the school to receive support. ŌĆ£It was a massive amount of remedial work that cost the local authority a fortune,ŌĆØ she says.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs particularly frustrating because this kind of emergency fix costs more in the long run than preventative maintenance,ŌĆØ she adds. But what can schools do? ŌĆ£Something has to go catastrophically wrong before you get funding to fix it.ŌĆØ

Reducing caretaking and cleaning

This situation poses challenges for multi-academy trusts when they take on new schools.

Adrian Ball, CEO of the Diocese of Ely Multi-Academy Trust, says the trust has ŌĆ£picked up schools where thereŌĆÖs been neglect around cleaning and planned preventative maintenance...which has then led to much greater increased costs in the long runŌĆØ.

For example, schools have ŌĆ£cut back on site staff so they havenŌĆÖt cleared the roof valley or cleared out the guttering, which then damages the fabric of the roofŌĆØ.

Ball says these kinds of issues are not uncommon, citing schools that - pre-conversion - had reduced their cleaning function or cut back on caretaking to the extent that the headteacher was responsible for locking the gate.

ŌĆśSomething has to go catastrophically wrong before you get funding to fix itŌĆÖ

Referring to a small primary school looking to join the trust, Ball says: ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve been told by the school leadership that when the cook is sick, the headteacher covers the kitchen.ŌĆØ

These experiences are familiar to Polley, who has only recently hired a caretaker again after three years without a site team.

ŌĆ£I just couldnŌĆÖt afford it, so I was doing it all myself. Now IŌĆÖve got two part-time cleaners for a vast site. I still havenŌĆÖt got dinner ladies or anything - the senior team do all the duties. I clean tables at lunchtimes.ŌĆØ

Polley says she makes this situation work, and, in fact, in her experience, ŌĆ£by having senior staff in key places, you lessen any silly behaviourŌĆØ from students over lunch.

Impact on leadersŌĆÖ mental health

But Ball worries about the long-term impact on leadersŌĆÖ mental health if they are continually picking up extra responsibilities far outside the usual headteacher remit. ŌĆ£Maybe they are the first one on site, the last one off site. ThatŌĆÖs a long day. ThatŌĆÖs the risk,ŌĆØ he says.

Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the NAHT school leadersŌĆÖ union, is more vociferous on how damaging he believes the situation is: ŌĆ£Leaders are already working intolerably long hours and should not be expected to take on other roles in the school as well,ŌĆØ he says.

ŌĆ£It is simply not in pupilsŌĆÖ best interests if [leaders] are being diverted from their core role of leading the school.ŌĆØ

If this predicament seems perilous for students in mainstream schools, the picture is even more concerning in the specialist sector, where the vulnerabilities of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) mean similar issues can pose even greater risks.

Lana Stoyles, executive director of business transformation at Nexus Multi Academy Trust, which runs 16 special schools, says a major safety concern in one Nexus setting is that the site is far too small for the number of children who attend, and there is no capital funding available to renovate.

The school building was originally a residential property, so certain safety features that a purpose-built school would have simply do not exist, she explains. ŌĆ£If you think about a standard school, you have a certain width of stairwell to make sure people can exit safely during a fire evacuation,ŌĆØ Stoyles says. But ŌĆ£this is a houseŌĆØ with a much narrower staircase.

ŌĆśDilapidated buildingsŌĆÖ in special schools

Meanwhile, at another school within Nexus, she says the ventilation system is ŌĆ£really oldŌĆØ and doesnŌĆÖt work properly, meaning that the building ŌĆ£gets extremely warm, and that can be triggering for some of the young peopleŌĆØ.

At another special school, one headteacher, who wishes to remain anonymous, has a similar problem.

ŌĆ£There is a high risk of [some students] having seizures because the ventilation and the classrooms get hot and the windows donŌĆÖt work properly,ŌĆØ they say.

This is just one of many concerns with their site - which they say was actually ŌĆ£condemnedŌĆØ 20 years ago. Since then the school has had all manner of structural and maintenance problems. ŌĆ£The roof is at the end of its life, so are all the windows and doors, and the boilers, heating and ventilation.ŌĆØ

ItŌĆÖs a similar story at another special school, with its business manager - who also prefers to remain anonymous - describing the state of the settingŌĆÖs ŌĆ£dilapidated buildingsŌĆØ: ŌĆ£We had three of our boilers fail last year, and we still have really old window walls that let in the cold.ŌĆØ

Combine these issues with the ever-increasing overcrowding of special-school classrooms - thanks to SEND tribunals directing children to settings that are already over capacity - and the risks for these vulnerable children are even greater.

ItŌĆÖs an issue that Pauline Aitchison, deputy director at Schools North East and network leader for the National Network of Special Schools for School Business Professionals, raised at a conference earlier this year.

ŌĆ£[Special-school] leaders really worry about being able to ensure the safety of children in environments where people canŌĆÖt afford the right staff, they canŌĆÖt afford the right resources to be able to support these children,ŌĆØ Aitchison said.

To close or not to close

Of course, leaders do have the right to close settings if they feel they are unsafe - but that itself is a ŌĆ£conundrumŌĆØ, as Andrew Banks, partner at law firm Stone King, explains.

ŌĆ£[There is a] juxtaposition between two things: their duty as an employer, as far as is reasonably practicable, to ensure the health, safety and welfare of their employees and people affected by their undertakings; and the necessity to keep the school operating and running.ŌĆØ

If a head does feel that the site is unsafe and doesnŌĆÖt have the funds to ensure the required health and safety measures, Banks advises undertaking a risk assessment, receiving expert opinions and making a decision based on that expertise.

This is what Chisholm did when one of her buildings reached a temperature of 53C. She has also previously closed a section of a playground when the school couldnŌĆÖt afford to have hazardous tree roots removed, and a prefab classroom when holes in the roof led to the electrics malfunctioning.

These closures add up, she says. In the infant setting, ŌĆ£weŌĆÖve had to close for 13 days over the past two years because of building and maintenance issuesŌĆØ.

Julia Harnden, deputy policy director at the Association of School and College Leaders, says she expects there will be ŌĆ£more occasions when [schools] have to ask at least some students to remain at homeŌĆØ because of the scale of the funding crisis.

ŌĆśThey canŌĆÖt afford the right resources to be able to support these childrenŌĆÖ

However, closing off access to school can itself pose a risk for students, as the anonymous special-school head explains: ŌĆ£If children have behavioural issues and parents are exhausted or unwell themselves, or if children are in small, overcrowded or mouldy housing, and theyŌĆÖre asthmatic, [thatŌĆÖs a risk]ŌĆØ.

Banks agrees that these additional potential dangers must be factored into a risk assessment before a decision is made to close any area of a school: ŌĆ£Are [students] better off being in an environment where they are being managed? Is that safer than the alternative?ŌĆØ

These are tough questions to ask, let alone answer - with Whiteman at the NAHT saying that this just proves how bad things have become.┬Ā

ŌĆ£School leaders should not have to strain so many sinews and face so many impossible choices when it comes to something as important as the safety and wellbeing of children and staff,ŌĆØ he says.

ŌĆ£There is no easy solution to these challenges other than for the current government to ensure that schools receive far more sustained funding for staffing and buildings.ŌĆØ

The next RAAC crisis?

But, given that education did comparatively well out of the last Budget, against other government departments, a big injection of funding seems unlikely, and some believe that action will only be taken after something disastrous happens.

Referring to the crisis around reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete, Warren Carratt, CEO of Nexus, says: ŌĆ£If we wait for it to be the next RAAC, we will be deliberately creating the context of knowing that children arenŌĆÖt accessing their legal entitlement to education, which is a very, very dangerous place for the system to be.ŌĆØ

Until then schools will continue to do all they can to keep children safe, even in these most dire of circumstances - because they have no other choice, says Polley. ŌĆ£We do what we need to.ŌĆØ

When Tes contacted the Department for Education to ask about its plans for solving this safety crisis, a spokesperson said: ŌĆ£This government inherited a school estate in dire need of repair, but we are committed to fixing the foundations for staff and pupils, turning the page on drift and neglect.ŌĆØ

They added that by 2034 the government will invest ŌĆ£almost ┬Ż3 billion per year...to improve the condition of school buildings, on top of the almost ┬Ż20 billion for the School Rebuilding Programme, delivering rebuilding projects at over 500 schools across EnglandŌĆØ.

You can now get the UKŌĆÖs most-trusted source of education news in a mobile app. Get Tes magazine on and on

Want to keep reading for free?

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just ┬Ż4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for ┬Ż4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for ┬Ż4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article