- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Secondary

- WhatŌĆÖs really going on with teenage girls?

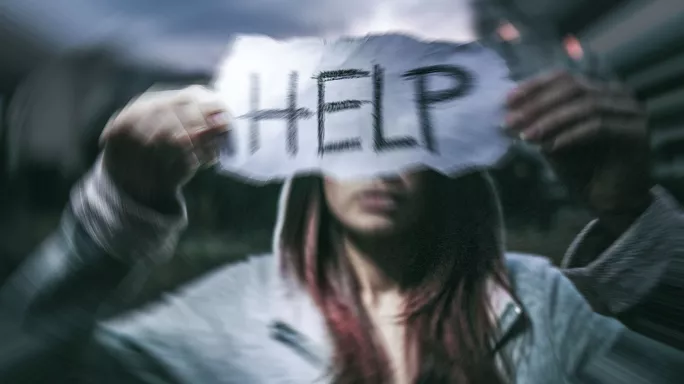

WhatŌĆÖs really going on with teenage girls?

What is happening with the mental health of older female students? The figures paint a stark picture.

The - which tracks around 19,000 young people born across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2000 to 2002 - found that at age 14, some 23 per cent of young women had self-harmed (compared with 9 per cent of young men). By the age of 17, that figure had risen to 28 per cent (and 20 per cent for young men).

And across all demographics, post-traumatic stress disorder is now .

Meanwhile, from the NSPCC for suicidal thoughts are girls, and suicide is the (and the fifth most common for boys).

Women of all ages are known to experience higher rates of depression and anxiety: some estimate that , while a reported that young women were three times more likely than young men to experience common mental health problems.

And these challenges can have multiple long-term consequences, from poorer educational outcomes to midlife health, and even early mortality.

GirlsŌĆÖ mental health: a new problem?

Despite many assuming otherwise, this gender imbalance is not new. Praveetha Patalay is an adolescent mental health researcher based at the MRC Unit for Lifelong Health and Ageing and the Centre for Longitudinal Studies at University College London, and she says that, while the overall prevalence of mental health challenges has increased in the youth population across the board in recent years, the gender gap has remained.

And as Tamsin Ford, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, states: ŌĆ£As long as thereŌĆÖs been psychiatric epidemiological data, teenage girls have been doing worse than teenage boys.ŌĆØ

So, why is this the case? ItŌĆÖs an area that is frustratingly under-researched, Patalay explains.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs an inherent assumption that it must be a biological thing,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£But people have tried to find clear biological markers, and there is very little good evidence for that. ThereŌĆÖs evidence that suggests it canŌĆÖt be purely biological, for example, looking at the gender gap in adolescent mental health across many countries.ŌĆØ

More on childrenŌĆÖs mental health:

- Why you canŌĆÖt separate attendance from mental health and SEND

- Mental health in schools: should we leave it to the experts?

- Why we must address emotional wellbeing at primary level

Patalay was part of of more than 550,000 adolescents across 73 countries, which found that girls do consistently have worse average mental health than boys across four key measures (psychological distress, life satisfaction, eudaemonia and hedonia).

However, if biology were the key factor, she explains, the gender gap would be similar across the world. And it isnŌĆÖt.

ŌĆ£The gap is actually really different across countries,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£There are some countries in which the gap is tiny [such as those in the Eastern Mediterranean], and some where it is very big, like in the UK. If it was a purely biological phenomenon, you would expect it to be more globally consistent.ŌĆØ

Interestingly, the gap is often larger in countries that are more gender equal - that is, where the rights and opportunities of men and women are more aligned. There are various sociological factors that could be feeding into this, Patalay explains.

ŌĆ£There is some evidence that girls in more gender-equal countries compare themselves to everyone, whereas in less gender-equal countries, girls compare themselves to girls and boys to boys.ŌĆØ

This could also be a question of expectation versus reality, she continues, where it may be ŌĆ£potentially worse to expect the world to not be patriarchal, sexist, and then find that the world constantly is, rather than growing up not expecting itŌĆØ. But, she adds, ŌĆ£we donŌĆÖt have any perfectly gender-equal countries where we can actually test these hypothesesŌĆØ.

The diagnosis difference

In addition to these sociological factors, there are also potential differences in how we diagnose behaviours in boys and girls that could affect the perceived prevalence of mental health challenges in each gender.

The received wisdom is that neurodevelopmental conditions (such as ADHD and autism) are more likely to affect boys, while emotional disorders (such as anxiety, depression and eating disorders) are more common in young women, explains Ford.

But this can bring disparity in mental health diagnosis, she continues, whereby we ŌĆ£underdiagnose and undertreatŌĆØ young women, especially in primary school.

She points to , also using the MCS data, in which ADHD symptoms between boys and girls in the UK were matched, but girls were found to be ŌĆ£less likely to be referred for treatment, and if they were seen for treatment, they were less likely to be given medicationŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs no clinical reason for that, because they were matching on the symptoms,ŌĆØ she continues. ŌĆ£But the ratio in the population is about three boys to one girl with ADHD diagnoses and itŌĆÖs similar for autism. By the time you get to clinics, itŌĆÖs nine to one.

ŌĆ£We know that boys are more vulnerable to neurodevelopmental conditions, but we donŌĆÖt seem to recognise girls with those difficulties.ŌĆØ

This means that at primary age, boys and girls are roughly ŌĆ£equally affectedŌĆØ in terms of mental health diagnosis, she continues, which is ŌĆ£probably about the balance of emotional disorders to neurodevelopmental disorders in the preschool and primary ageŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£But by the time you get to early teens, the girls start taking off,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£When I was a trainee, you could see it because we had different colour folders, green for boys and buff for girls. The clinics that focused on primary school kids were nearly all green folders, and the other side of the shelf, which was dealing with adolescents, were nearly all buff folders.ŌĆØ

The after-effects of the pandemic

How did the Covid pandemic - so often cited as a significant cause of mental health challenges in young people - affect this pre-existing gender split? The lockdowns appear to have ŌĆ£amplifiedŌĆØ an existing trend, Ford says.

The incidence of eating disorders saw a particular spike, with one study finding that than would be expected for girls aged 13-16 in the two years after the pandemic began, and 32 per cent higher for girls aged 17-19. Diagnoses in boys, however, remained broadly as expected.

Meanwhile, found the likelihood of girls ŌĆ£hiding poor mental health or distressŌĆØ had risen from 60 per cent to 80 per cent since the start of the pandemic. The same report also highlights ŌĆ£unhealthy perfectionismŌĆØ and ŌĆ£extreme self-controlŌĆØ having increased from 20 per cent to 80 per cent.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not that itŌĆÖs a novel pattern: itŌĆÖs an accentuated pattern,ŌĆØ Ford explains. ŌĆ£As we went into the pandemic, weŌĆÖd already had a deterioration from the beginning of the century in terms of the numbers of youngsters with anxiety and depression, and that was affecting girls more.

ŌĆ£But in the follow-up surveys over Covid, the increase in the prevalence of mental health conditions is in all age groups and both genders, but itŌĆÖs accentuated in teenage girls. And those conditions are often self-harm, anxiety, depression and eating disorders.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśI donŌĆÖt think weŌĆÖre going to put the social media genie back in the boxŌĆÖ

What about the impact of social media? Phones, and what young people do on them, have been widely cited as a trigger and accelerator of mental health issues, particularly among girls.

However, this is in need of more research, Ford argues.

ŌĆ£Some research finds that young people with poor mental health spend more time on social media and feel more negatively about their experiences while using it but nearly all this work is cross-sectional,ŌĆØ she explains.

ŌĆ£If young people reported their social media use and mental health at the same time, we donŌĆÖt know if poor mental health is the cause or result - so this suggested link doesnŌĆÖt necessarily mean causality.

ŌĆ£If youŌĆÖre anxious and depressed, you might be going online more because of that. We need longitudinal studies that follow young peopleŌĆÖs mental health and social media use over time, and we donŌĆÖt have very many of them.ŌĆØ

She adds that there is ŌĆ£no doubt that for anorexia and self-harm, for example, there are some absolutely awful sites that you donŌĆÖt need any kind of research to demonstrate that they really ought to be blocked or taken down as theyŌĆÖre promoting both conditions as an acceptable lifestyle choice, and many are very, very graphicŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£But I donŌĆÖt think weŌĆÖre going to put the social media genie back in the box,ŌĆØ she adds. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs going to be like cars: weŌĆÖre going to have to help people to negotiate using them safely, as far as we can.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśA linear relationshipŌĆÖ

Others, though, are more convinced of a negative directional link. John Gallacher is professor of cognitive health at the University of Oxford and is leading on , a 10-year research project that is looking to recruit 50,000 young people across the UK.

The project is still in its infancy, but already hit the headlines in October with an early finding that young people are spending as many as eight hours a day on their phones, and that there is a ŌĆ£a linear relationship between higher rates of anxiety and depression and time spent networking on social media sitesŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£It may not be directly causal because these things are complex, but nevertheless, it would be very surprising to me if you stopped using your phone and your mental health did not improve,ŌĆØ Gallacher says. ŌĆ£We are setting up trials to explore that because otherwise there will always be the debate over the direction of causation.ŌĆØ

The Australian government, too, seems convinced, recently announcing under the age of 16.

Does social media affect girls more than boys, though? While the negative effects will hit all young people, research suggests that from social media use than boys, particularly in relation to sexualised pictures and self-image.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not that boys are immune,ŌĆØ Gallacher continues. ŌĆ£Our data shows that social media use is correlated with higher anxiety in boys as well. But if you have an overall lower level of anxiety, as boys do, the impact isnŌĆÖt as great.

ŌĆ£I think itŌĆÖs really, really hard to be a young girl these days. The pressures on you in terms of your look and your social prestige are enormous, and often entirely unrealistic.

ŌĆ£And a thing about social media is that whatever is considered perfect at the time gets promoted, whereas in oneŌĆÖs smaller real-world ecosystem thereŌĆÖs a much better sense of perspective, not just in terms of the breadth of data that you have but the depth of data.ŌĆØ

Aside from social media, sociological forces and diagnosis issues, what other forces that affect mental health may be affecting girls more acutely?

There are myriad other well-known risk factors for poor mental health in all young people, explains Patalay, including ŌĆ£genetic predisposition, poverty, violence and behaviours like being sedentary, smoking and taking drugsŌĆØ, but itŌĆÖs as yet unknown exactly how these affect young women and men differently.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre doing a big multi-country project at the moment to look at risk factors for mental ill-health, but women might experience more of them so theyŌĆÖre disproportionately affected.ŌĆØ

She offers the example of sexual violence, which is five times more likely to be experienced by young women than young men: a 2022 analysis of the MCS found that in the previous 12 months.

ŌĆ£Essentially, sexual violence in adolescence is bad for mental health for both girls and boys but girls experience it far, far more. So on the population level, itŌĆÖs worse for girls because more women experience this risk factor.ŌĆØ

ŌĆśItŌĆÖs really, really hard to be a young girl these days. The pressures on you are enormousŌĆÖ

Alongside all this complexity you have education. What role are schools playing in the mental health of girls? Can they help reduce the imbalance in their female students, or do they accelerate it?

Patalay says that while more research is needed into protective factors for young peopleŌĆÖs mental health, found the significant impact that schools can have.

It found that a ŌĆ£more positive school climateŌĆØ meant almost 25 per cent less chance of having ŌĆ£high levels of difficultiesŌĆØ with ŌĆ£emotional and behavioural symptomsŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£What we found is probably what youŌĆÖd expect: in schools where children feel connected and safe, and where they can speak to an adult in the school, young peopleŌĆÖs mental health was better,ŌĆØ she explains.

ŌĆ£But we also found what we call an interaction with gender, where the effect of a better climate was stronger for girls than boys.

ŌĆ£Again, itŌĆÖs good for everyone, but itŌĆÖs possible that itŌĆÖs more protective for girls because they are more vulnerable to emotional symptoms and distress at that age.

ŌĆ£Increasing those protective factors is good for everyoneŌĆÖs mental health, but itŌĆÖs possible that some of them will disproportionately end up being better for girls.

ŌĆ£But thatŌĆÖs OK, because many, many more girls are struggling with their mental health.ŌĆØ

The importance of referrals

Ford likewise highlights the importance of good relationships for good mental health (for girls and boys), particularly around ŌĆ£school connectedness and being actively engagedŌĆØ.

And where staff are seeing issues, she continues, itŌĆÖs important to refer to experts, even while waiting lists are long (a 2024 report found that to be seen by Camhs).

Ford points to the many excellent resources of support available - including the , and a new self-harm support resource developed by members of her team, entitled - but says referrals should still be made.

ŌĆ£I would still be referring because we canŌĆÖt just pretend itŌĆÖs not there,ŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£We wouldnŌĆÖt if it was diabetes or cancer, so we shouldnŌĆÖt for mental health either. Camhs is seeing more people, but the problem is that the number of people needing seeing has increased faster.

ŌĆ£If a school doesnŌĆÖt have a mental health support team, they should be thinking about getting some kind of mental health intervention on site, because poor mental health gets in the way of how people can access education.ŌĆØ

Ultimately, the reasons for the mental health struggles experienced by teenage girls are complex and firm conclusions about their drivers are, as yet, elusive. Popular wisdom suggests that social media may be playing a role, but it would be an oversimplification to believe itŌĆÖs the sole culprit.

Amid the intricate interplay of societal pressures, biological factors and individual experiences, more research is needed, along with greater awareness of what life is really like for these young women. It seems there will be no easy fixes; instead, it will require investment in comprehensive support systems, including accessible mental health services, and a focus on fostering genuine connections within communities.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article