- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Secondary

- Why subjects need their own take on the ŌĆścogsci revolutionŌĆÖ

Why subjects need their own take on the ŌĆścogsci revolutionŌĆÖ

It is not that long ago that you would still hear people arguing that ŌĆ£a good teacher can teach anything wellŌĆØ.

Happily, the general consensus in secondary schools these days seems to have shifted towards an understanding that even the most effective teacher of one subject cannot simply be expected to translate their skills seamlessly into another.

Teaching is a hugely complex and context-dependent pursuit, and different subjects all have their own particular nuances; the most carefully and thoughtfully ŌĆ£evidence-informedŌĆØ teacher in one subject may find that their strategies donŌĆÖt immediately guarantee success in another.

Recent research supports this position.

Subject-specific pedagogy

A study looking at which classroom activities were most important for GCSE success found that, for English teachers, it was facilitating interaction and discussion between classmates. In maths classes, however, the key activity is making time for students to practise questions individually in class ().

Another study examining geography, maths and languages suggested that different ŌĆ£evidence-basedŌĆØ learning strategies may be more effective for different subjects ().

Many school subjects also have a rich and established culture of disciplinary research and pedagogy, which should be valued and celebrated.

Cognitive science in schools

All this raises an important - and under-explored - question: if we accept that subject specificity is hugely important, then what are we to make of the ŌĆ£cognitive science revolutionŌĆØ in education, with its insights into the general mechanisms of learning often coming from non-classroom studies, or studies of subjects other than our own (unless youŌĆÖre a maths teacher; see )?

Are the general insights negated by the disciplinary nuances? Or do they supersede them?

How can we reconcile the fundamentals of learning with the characteristics of our own disciplines in order to develop an evidence-informed model of subject-specific teaching?

We would argue that taking an evidence-informed approach to teaching a subject involves designing learning experiences that take into account both what we know about how we learn in general and also the nuances and structures of the subject.

We therefore start with two fundamental questionsŌĆ”

- What do we know about how people learn in general?

- What are the specific features of my particular discipline that affect how we learn it?

ŌĆ”in order to help us answer a third question (the one that is in factthe mo st important): - What should I actually do in my classroom?

Our teaching framework

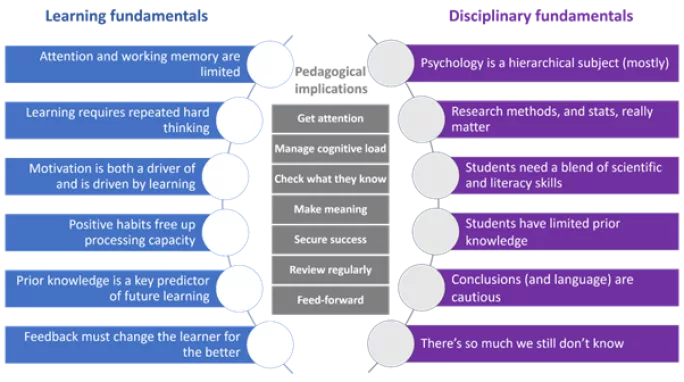

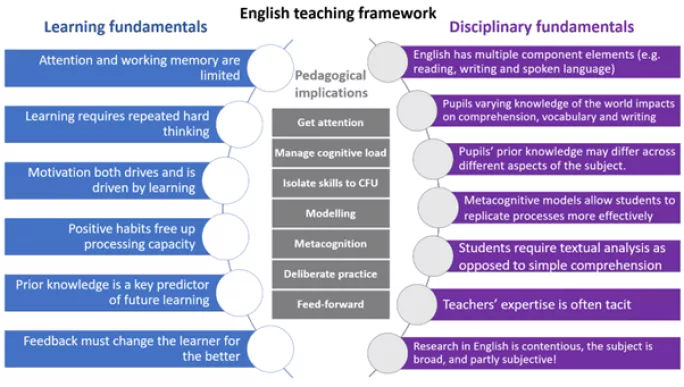

In our forthcoming book on psychology teaching, we represent this model in the form of a ŌĆ£psychology teaching frameworkŌĆØ, with six ŌĆ£learning fundamentalsŌĆØ and six ŌĆ£disciplinary fundamentalsŌĆØ combining to produce seven ŌĆ£pedagogical implicationsŌĆØ for psychology teaching specifically.

You can see this below:

But does this way of representing evidence-informed teaching work for other subjects? And how would the model look when adapted to different subject areas?

Hierarchical knowledge

The sociologist Basil Bernstein differentiated between two different methods by which the knowledge of an academic subject can be organised.

Hierarchical (or ŌĆ£verticalŌĆØ) subjects are those in which ŌĆ£general propositions or theoriesŌĆØ are applied to, and used to explain, new knowledge (which is therefore built on top of these general foundations, in a hierarchy).

Classic examples of hierarchical subjects tend to be the sciences and maths.

In contrast, more ŌĆ£horizontalŌĆØ subjects may use different modes of enquiry, perhaps with different key principles and terminology, in different areas of the subject. Many humanities subjects are argued to fit this description.

This difference has wide-ranging consequences for subjects.

While the structure of the subject is a disciplinary fundamental, the implications that this places on learning affect the pedagogical implications, and even the learning fundamentals that we think are most important for the teaching of the subject.

Science and maths teaching

LetŌĆÖs look at science first.

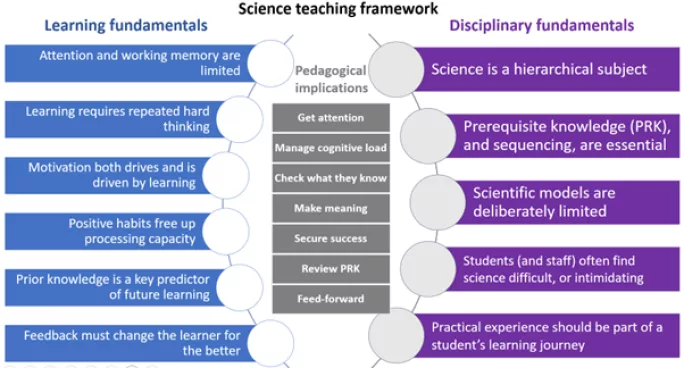

Claudia Allen, a lead practitioner for science, points out that her subject is ŌĆ£very hierarchicalŌĆØ, and that as a result, ŌĆ£students need to have the correct knowledge on which to buildŌĆØ.

The implications of this are to place even greater importance on securing prerequisite knowledge - prior knowledge that is foundational and therefore essential for new learning.

As a result, her science teaching framework (below) places greater emphasis on this, both in an additional disciplinary fundamental and in adjusting our original pedagogical implication of ŌĆ£review regularlyŌĆØ to be ŌĆ£review prerequisite knowledgeŌĆØ.

Other hierarchical subjects, such as maths, also have similar considerations.

Steven Sheppard, a subject leader for maths, highlights the importance of strong foundations and their effects on subsequent pedagogical choices. This is why approaches such as ŌĆ£mastery learningŌĆØ tend to be used far more in hierarchical subjects.

Sheppard suggests ŌĆ£interweaving is required for masteryŌĆØ as a disciplinary fundamental, leading to two specific pedagogical implications of ŌĆ£interleavingŌĆØ and ŌĆ£embed in different contextsŌĆØ.

ŌĆśDoingŌĆÖ geography

So, what about more horizontal subjects?

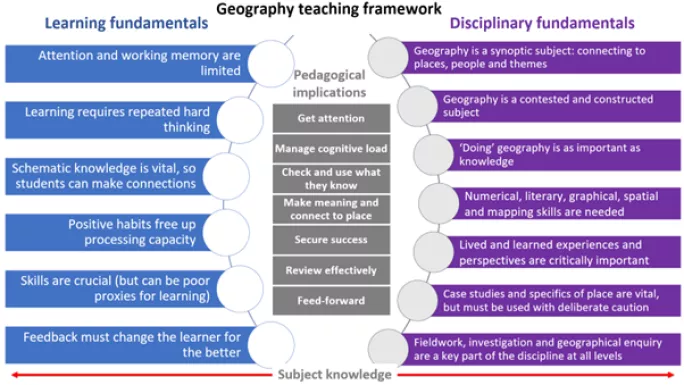

David Preece, head of geography teacher education at Teach First, suggests that ŌĆ£geography is a synoptic subjectŌĆØ, that ŌĆ£ŌĆśdoingŌĆÖ geography is as important as knowledgeŌĆØ and that from these disciplinary fundamentals even some of the learning fundamentals of the subject are different, including ŌĆ£schematic knowledge is vital, so students can make connectionsŌĆØ and ŌĆ£skills are crucial (but can be poor proxies for learning)ŌĆØ.

This also leads to differences in pedagogy. The role of knowledge-focused retrieval practice becomes less clear. As Preece says, ŌĆ£the ŌĆśskillsŌĆÖ are about the only thing you can regularly and effectively thread through all of your curriculum or topic units with anything approaching consistencyŌĆØ.

This requires that teachers ŌĆ£make deliberate and intentional decisions about curriculum choices and case study examplesŌĆØ and leads to the pedagogical implication that they ŌĆ£review effectivelyŌĆØ rather than just ŌĆ£regularlyŌĆØ.

History: teaching through story

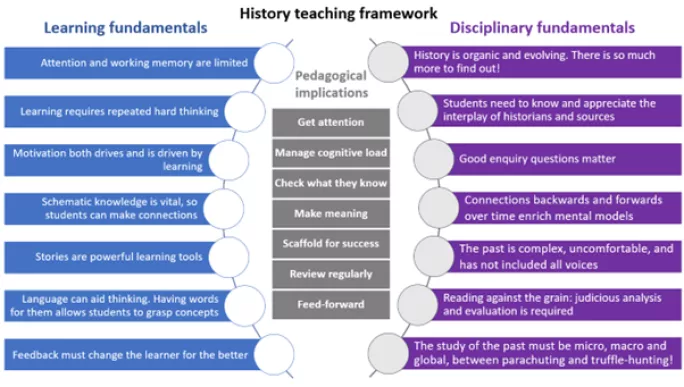

Similarly, Alex Fairlamb, a trust teaching and learning network lead for history and an assistant principal, highlights disciplinary fundamentals such as ŌĆ£students need to know and appreciate the interplay of historians and sourcesŌĆØ, ŌĆ£connections backwards and forwards over time enrich mental modelsŌĆØ and ŌĆ£the study of the past must be micro, macro and globalŌĆØ.

These are challenging skills that take time to build in our students, emphasising the need to ŌĆ£scaffold for successŌĆØ as a pedagogical implication.

Elizabeth Carr, assistant principal and a curriculum and subject lead for humanities, also suggests that history teachers take advantage of the fact that ŌĆ£our brains are particularly attuned to stories, and particularly to character, conflict, causality and complicationsŌĆØ.

She also highlights how any pedagogical implication, even if seemingly shared between subjects, will look different once filtered through the specifics of the discipline.

For example, ŌĆ£manage cognitive loadŌĆØ in history could include ŌĆ£teaching vocabulary that enables students to think about concepts, or teaching through storyŌĆØ.

PE pedagogy

The acid test of any system of evidence-informed teaching, of course, is whether it is flexible enough to accommodate those unicorns of the school system: PE, music and art.

Beyond the surface-level differences with much of the rest of the school timetable, another of the challenges of producing a coherent evidence-informed model of teaching in these subjects is that they have multiple component parts that may require different approaches.

So, can our model accommodate such diversity?

PE teacher Zeph Bennett thinks that it can be adapted successfully for PEŌĆ” mostly.

He observes that there are three main domains to acquiring new movement skills in PE: psychomotor (development of movement skills and abilities), cognitive (developing understanding and awareness of movement) and affective (communication and the social and emotional skills required to play sport).

The learning framework as presented lends itself better to psychomotor and cognitive, but somewhat less so to the affective, around which there is less of a research base.

Music lessons

Similarly for art and music, Naomi Pilling, a curriculum adviser for the Primary Knowledge Curriculum, suggests that both subjects divide into ŌĆ£practicalŌĆØ (knowing how to do something) and ŌĆ£theoreticalŌĆØ (understanding the underlying ideas) components, and that while the same learning fundamentals might govern both, they may require different pedagogical approaches at different times.

Building on this, Niklas Rudb├żck, PhD in arts education and a lecturer in music education at the Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg, suggests that while the pedagogical implications suggested in the original model remain mostly valid for music teaching, their importance might vary ŌĆ£depending on the age of the students, aims of the lesson, available time and equipmentŌĆØ.

Rudb├żck suggests that disciplinary fundamentals for music might include ŌĆ£music is invisibleŌĆØ, ŌĆ£music consists of change and patterns extended in timeŌĆØ and ŌĆ£music is a sounding art form, which means that listening is central to all musical activitiesŌĆØ.

These features make implications such as ŌĆ£get attentionŌĆØ especially pertinent and challenging, as ŌĆ£there are aspects of music that canŌĆÖt be held still to help us attend to them, especially metrical and rhythmical aspectsŌĆ”ItŌĆÖs unusually reliant on different means of representing musical sounds in other modes (verbally, bodily, graphically, etc). We need these representations to help us point to the music, ŌĆśhold it stillŌĆÖ and find patternsŌĆØ.

Teaching English

Diverse components are not solely a feature of art, music and PE. English is another subject with multiple component skills, building up to two entirely separate examined subjects at GCSE and A level.

Zoe Enser, English teacher and school improvement lead at the Education Partnership Trust, argues that ŌĆ£pupilsŌĆÖ prior knowledge will be limited in different ways across different aspects of the subjectŌĆØ.

ŌĆ£For example, verbally, they may be very confident but then have limited understanding of how to construct a sentence, or they may be able to decode but have issues with fluency or have a lack of access to a wide range of background knowledge, which will impact on comprehension.ŌĆØ

As a result, a pedagogical implication is that English teachers need to be adept at isolating different skills when checking understanding and performance.

Composition and writing

One further implication from this is that ŌĆ£the speed at which pupils are required to move into composition [which requires many of the component skills simultaneously] is often a pedological problem that needs to be solvedŌĆØ, as there are ŌĆ£challenges in ensuring pupils have the required knowledge of texts, topic and grammatical construction to ensure they are able to compose an effective pieceŌĆØ.

As a result of this, Enser suggests a two-stage approach to evidence-informed English teaching, with an early hierarchical phase focusing on ŌĆ£phonics, transcription and grammarŌĆØ, followed by a more horizontal phase focusing on ŌĆ£the interplay between different elements of the subject [such as] reading, writing and spoken languageŌĆØ.

Common challenges

Nearly all our respondents highlighted a lack of time as a potentially confounding factor in the implementation of models such as the above.

Fairlamb points out that the ŌĆ£time within departments to work together to form an understanding of such a model is limitedŌĆØ, especially given other competing priorities in CPD calendars and the fact that many teachers might be teaching multiple subjects.

Allen also notes the lack of time within lessons to properly implement the pedagogical implications; for example, the challenge of balancing the need to revisit prerequisite knowledge with the need to progress through an overstuffed curriculum.

Would the ongoing curriculum review be more successful if it were properly informed by these kinds of models/discussions?

Preece also suggested that our original model had neglected subject knowledge. Teacher subject knowledge is often split into ŌĆ£content knowledgeŌĆØ (knowledge about the subject area in general) and ŌĆ£pedagogical content knowledgeŌĆØ (knowledge related to the teaching of the subject), both of which may contribute independently to student outcomes ().

Pedagogical implications

The pedagogical implications in our model illustrate examples of pedagogical content knowledge, but there is certainly space for the additional consideration of content knowledge, which on its own is still an important factor in teacher effectiveness and student achievement ().

Indeed, this may be even more important in more horizontal subjects, such as geography, where the variance in possible approaches means that ŌĆ£two students who are theoretically doing the same paper can have completely different topics, content and ideasŌĆØ.

This can make it harder to find ŌĆ£commonality and shared ideasŌĆØ.

The process matters

From the above, itŌĆÖs clearly unlikely that we will ever hit on a framework that all teachers of the subject will agree on. Perhaps thatŌĆÖs all the more reason to try, however.

The outcome here is not always the most important thing. The value is the process of creating a teaching framework, and the benefits that follow from it. First and foremost, taking an evidence-informed approach can help us to shape effective learning experiences for our students. But that is not the only reason.

One important secondary benefit is that of motivation for further professional learning. It is sometimes claimed that the use of evidence in education can be a tool to deprofessionalise teachers and to reduce us all to identikit approaches.

Nothing could be further from our experience. Having a coherent and empirically grounded framework for our teaching has allowed us to analyse our practice in more depth, and with greater specificity, than we ever had previously.

Motivation in our jobs not only makes it more likely that we will do them well, but motivated teachers are less likely to suffer burnout ().

In a related finding, first-year teachers who are using evidence-informed pedagogical strategies have been found to report higher levels of school-based wellbeing ().

A final benefit for us as teachers is confidence. If we know exactly why we are making a particular pedagogical change, and what we expect the benefits to be based on both learning and disciplinary fundamentals, then we can approach our classroom activities and our professional development much more effectively.

Michael Hobbiss and Paul Cline are the authors of How to Teach Psychology: an evidence-informed approach, available

For an indispensable look at the weekŌĆÖs biggest stories and talking points, sign up for our Weekly Debrief newsletter

Want to keep reading for free?

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just ┬Ż4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for ┬Ż4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for ┬Ż4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article