In recent years, tests in maths have become the go-to method for identifying progress. But how much do we really learn from a test? Is there a better way to provide information about childrenâs understanding that enables teachers to support their learning?

Research shows that a âclinical interviewâ approach can transform assessment by providing information not only on childrenâs performance and knowledge but also their potential, attitudes and motivation. This highlights the need for teachers to know more about childrenâs thinking, which is not demonstrated by writing a number in a box.

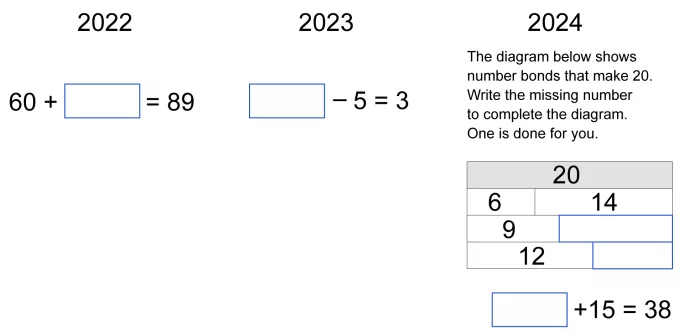

Taking the test below as an example, whether children respond correctly or incorrectly, we donât know if they are answering using number bonds, place value or simply counting on or back in ones. This significantly limits the usefulness of such tests in evaluating overall mathematical competency.

Ìę

Ìę

What tests do offer is a quick way of providing data for accountability. But we can use assessment tasks to inform planning and provide data. If teachers use carefully designed tasks, ask targeted questions and look and listen to pupils, they gain a wealth of information about their mathematical skills and understanding.

And so members of the and the have put together a suite of . These are aligned with the national curriculum and provide opportunities for childrenâs discussion and recording.

Here is one example:

Primary maths assessment: the hiding game

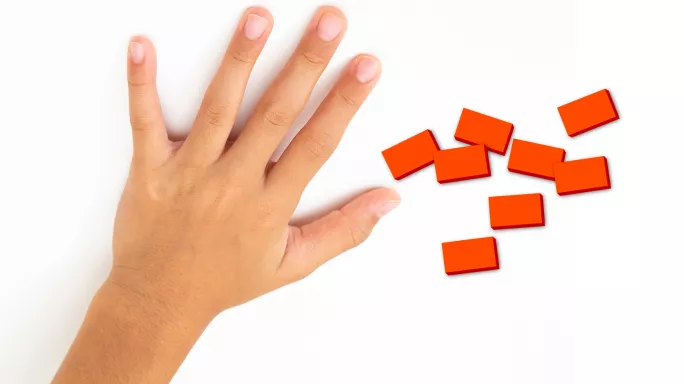

Pupils work in pairs using 10 ten-rods and 10 ones. The teacher models the game with a chosen number of ones, while the children watch. Then the children close their eyes, the teacher hides a few ones under their hand, then children open their eyes and work out how many are hidden from how many remain in view.

Ìę

The children then play with a partner, taking turns:

Game one: Each time they play, they decide on a total number of ones to work with. Once children are playing the game comfortably, they decide on a way to record each turn, first in their own way and later using some or all of the following symbols to record: + - =

Game two: Extend to other amounts; for example 20, using one ten-rod and 10 ones.

Game three: Using only 10 ten-rods, work with multiples of 10 within 100.

Ìę

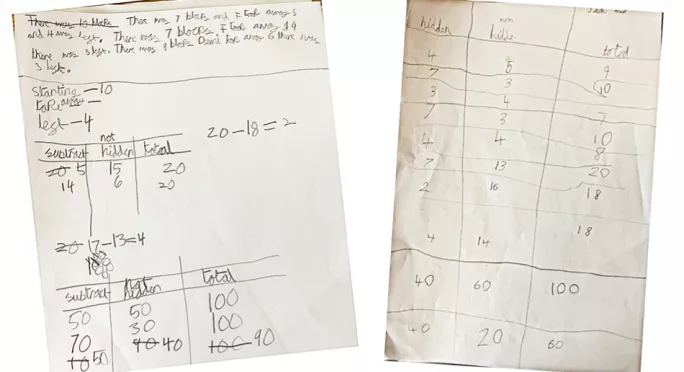

Here, the child starts by using text to document the game. When prompted by the teacher: âCan you find another way to record the game?â, they demonstrate that they know how to tabulate, and, later, how to record as an equation.

The may revert to using a table for the third game, which may indicate that they feel more comfortable recording this way. The child is also able to clearly relate the role of each of the numbers in the equation to the game.

More on primary maths:

A child might choose to record as a table, but interprets the situation as a missing number addition, demonstrating fluency in the use of inverse.

Teacher: âHow did you know how many were hidden each time?â

Pupil: âSome were taken away, but I had to take away the other number.â

Teacher: âCould you record each turn a different way?â

Pupil: âIt could be adding, so I could say 4 plus 5 equals 9â.

This is a good time to use tasks more than tests. Sats are no longer a statutory requirement in key stage 1, so there is now a wonderful opportunity for schools to reconsider the purposes of assessment.

Tasks such as these offer teachers a more informative alternative to a test, using teacher questioning to highlight areas that are firmly understood and those that need more teaching.

Janine Blinko, Alison Borthwick, Pip Huyton and Helen J Williams are members of the UK Joint Primary Group of the Association of Teachers of Mathematics and the Mathematical Association