It was 2006, and IÌýwas the newly installed schools minister, sat in my office in Sanctuary Buildings, when I recieved a message that Tony Blair wanted to see me in his office at Number 10. This hadÌýnever happened to meÌýbefore, as my previous role in the backwaters of the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs had never captured his attention.

Next minute, I was sat on one of Prime Minster’sÌýfamous sofas, alongside the new Secretary of State at Defra,ÌýDavid Miliband, and the public health minister Caroline Flint.

Tony wanted to.

He told us that we had three months before he was appearing on Jamie’s TV programme about schoolÌýdinners and, right at that moment, he hadÌýnothing worth saying. What could we come up with? Caroline andÌýDavid were experienced ministers and therefore both turned away from Tony and looked at me.

I walked away from the meeting with a prime-ministerial mandate to work across three governmentÌýdepartments to put together a five-point plan. Lists always came in threesÌýbut plans, like pledges,Ìýalways came in fives. As a result,Ìýwe had new nutritional standards, fundingÌýfor school kitchens, noÌýfizzy drinks machines, chips only once a week and the important fifth point in the plan.

That was the moment I realised that my new job had real power, but celebrity chefs still might haveÌýmore…

I only had one year working for Tony as schools minister, before survivingÌýthe transition to Gordon,Ìýbut in that time one of the drivers of attention was publicity. IÌýwas responsible for Building SchoolsÌýfor the Future, and remain very proud of the community transformation itÌýdelivered, especially inÌýBristol where it was delivered in full. However the new buildings did alsoÌýserve well as greatÌýbackdrops to prime ministers wanting to project future and regeneration.

Publicity was not always positive. My education secretary, Alan Johnson,Ìýand I attracted the PrimeÌýMinister’s attention over faith schools. David Cameron’sÌýfirst leader’s speech at party conference was all about repositioning the Tories asÌýbeing more inclusive. He encouraged church schools to open their admissions to children of otherÌýfaiths. Alan and I saw a political opportunity to go a bit further than the Opposition and mandateÌýsuch a move. Alan got clearance from Number Ten to float the ideaÌýas long asÌýweÌýhad our ducks inÌýa row.

Sadly the ducks turned out to be less orderly than we thought, andÌýwe had a bit of an argument. TheÌýMonday after what appeared to be a concerted attack on us from the pulpit,Ìýwe not only hadÌýswathes of Labour MPs with large Catholic communities descending on usÌýin the voting lobbies, weÌýhad a highly irritated prime minister. We quickly performed a delicate three-point turn.Ìý

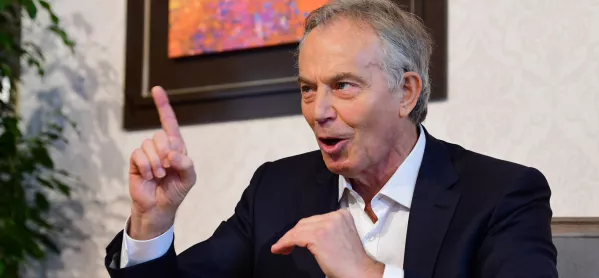

But Tony was not all surface -Ìýthere was a lot going on below the waterline, too.Ìý

I remember holding a constituency surgery in Weymouth Library when he first rang meÌýto offer me the job asÌýschools minister. After I gratefully accepted, his one piece of advice in dealing with this bigÌýpromotion was to work closely with Andrew (now Lord) Adonis.

Not only was this good advice,Ìýas Andrew was an exceptional minister at getting things done, it wasÌýalso code:Ìýmake sure the academies programme delivers.

I took over in the middle of a big rowÌýabout the schools White Paper and trust schools (whatever happened to them?),Ìýand I was straight into steering the onto the statute book. Despite the internalÌýopposition led by John McDonnell (now shadow chancellor), we got there easily enough.

My role soon became one of using my charms to ease through our structural reforms in theÌýCommons, with the unions and in the media, whileÌýAndrew didÌýthe heavy lifting.

IÌýalso drove hardÌýonÌýteacher recruitment and pay, school leadership, BSF, effective use of technology, parentalÌýinvolvement and the ill-fated diploma programme. My day-to-day handling from Tony came in theÌýform of his highly effectiveÌýadviser, Conor Ryan. Conor would appear and gentlyÌýadvise me of the prime minister’s concerns and I would respond appropriately.

But on academies,Ìýwe had occasional prime ministerial stocktakes with Tony around the cabinet table. He drilled into the detail, looked you in the eye, and properly held you to account. My recollection of his exasperation in these meetings was that it was mostlyÌýpointed towards hisÌýneighbour next door in Number 11.

I remain proud of Tony’s record in education. There were mistakes, especially around the Tomlinson Review, but things got better. The literacy and numeracy hours lifted primary results for the firstÌýtime in a generation, Every Child Matters and Sure Start were brilliant.

The London Challenge andÌýextended schools worked well. And as I visit schools now that is whatÌýmany teachers tell me weÌýachieved: more staff, better paid, better led and trusted more, with litter bins being used to catchÌýwaste paper and not leaks from the ceiling.

Tomorrow’s Tes magazine, available in all good newsagents,Ìýhas a cover feature analysing Tony Blair’s legacy in schools.ÌýTo download the digital edition, Android users canÌýÌýand iOS users canÌý

Jim Knight is chief education adviser to TES Global

Ìý