How one trust closed its disadvantage gap

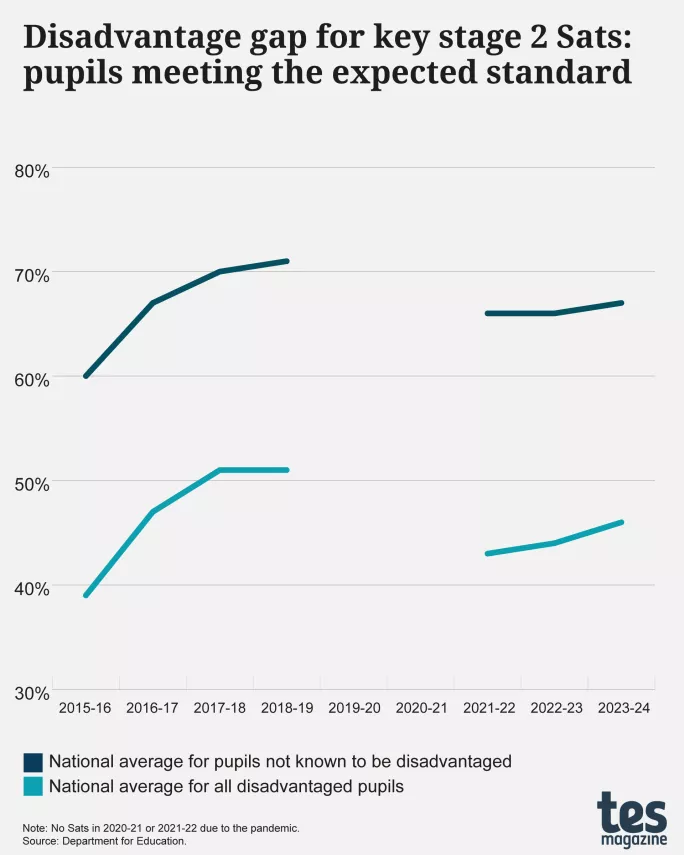

In the last nine years, the gap between disadvantaged pupils and pupils not known to be disadvantaged who met the expected standard in reading, writing and maths at key stage 2 Sats has never been any narrower than 19 per cent.

Furthermore, while some progress had been made in increasing the overall number of disadvantaged pupils hitting the expected standard, the pandemic set back progress - and, although it is slowly climbing again, it is still a lowly 46 per cent.

╠²

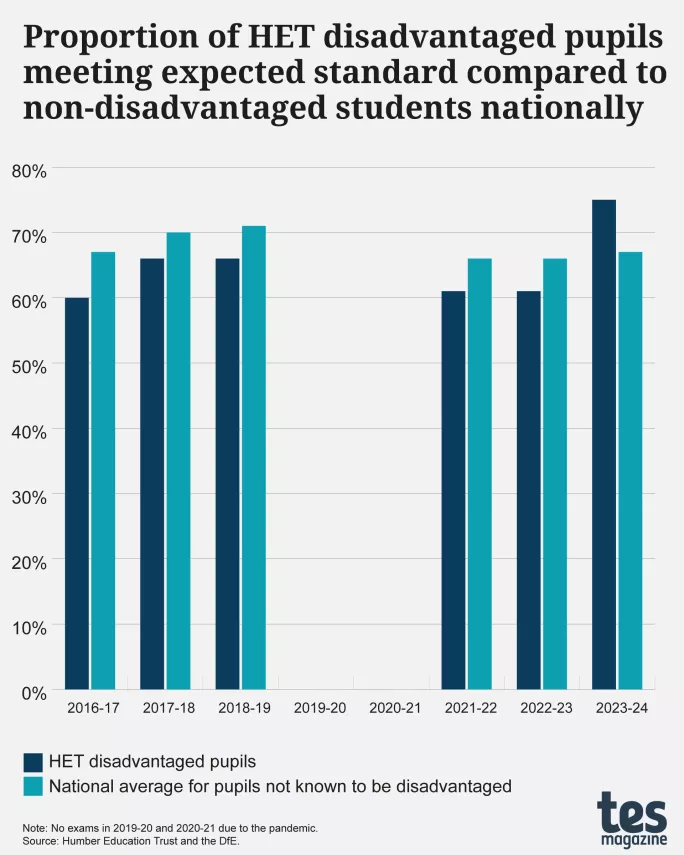

But at Humber Education Trust (HET), home to two special schools and 13 primary schools, the disadvantage gap for pupils in those primary schools has been positively slammed shut, after the latest figures show 75 per cent of disadvantaged pupils meeting the expected standard in all subjects (reading, writing and maths) combined.

This is 29 per cent higher than the national average for disadvantaged pupils - and eight per cent higher than the national average for pupils not known to be disadvantaged. The data represents a milestone moment for the trust as part of a long-term drive to eradicate the disadvantage gap.

╠²

╠²

It is data that will make other leaders, and policymakers, sit up and take notice and wonder what the secret is. Rachel Wilkes, chief executive of HET, spoke to Tes to explain some of the core decisions made to help achieve this outcome.

1. Culture changes

The first thing the trust did was to ensure its culture aligned with the goal of closing the disadvantage gap - something many trusts will no doubt aim to do, but that Wilkes says required tackling the reality that not everyone was on board with this vision.

ŌĆ£[There would be] pupil progress meetings with a teacher saying, ŌĆśthese are the children that arenŌĆÖt on track [ŌĆ”] and theyŌĆÖre not going to get it because they are disadvantagedŌĆÖ and ŌĆśno-one listens to them read at homeŌĆÖ - and we had to say ŌĆśis that really what weŌĆÖre saying, that we canŌĆÖt help? If no one is hearing them read at home are we making sure we hear them read in school?ŌĆÖŌĆØ

Linked to this shift in mindset was a clear sense of expectations for pupil outcomes.

ŌĆ£The target is 100 per cent - why wouldnŌĆÖt the target be 100 per cent? As soon as you say to a teacher your target is 75 per cent then you have agreed 25 per cent are not going to get it.ŌĆØ

Finally, the trust wanted to move away from using interventions and catch-up as the solution to improving disadvantaged pupil outcomes: ŌĆ£An intervention is a sticking plaster,ŌĆØ says Wilkes.

ŌĆ£If youŌĆÖre really clear about what you want children to learn in every single year group, and make sure every person they interact with knows their stuff and is well trained, that cumulative impact is what makes the difference.ŌĆØ

2. Developing teacher expertise

That view led to one of the big changes within the trust - a move away from using data targets for staff appraisals and towards something more holistic: ŌĆ£We wanted to ask, ŌĆśare you doing your job really well?ŌĆÖŌĆØ, says Wilkes.

So the trust turned to the TeachersŌĆÖ Standards as its framework for good teaching - but realised, ŌĆ£we had no clear shared understanding of what meeting the TeachersŌĆÖ Standards meantŌĆØ.

So the trust created its Teacher Development Program that aimed to ensure ŌĆ£every headteacher, every leader, every classroom teacher [ŌĆ”], every member of support staffŌĆØ had a really clear understanding of ŌĆ£what great pedagogy meansŌĆØ, Wilkes says.

This approach allowed appraisals to focus on the question ŌĆ£are you meeting the TeachersŌĆÖ Standards?ŌĆØ and how this linked to its desire to improve outcomes for all pupils - and, if not, offer the support needed to improve.

3. Teaching skills

Ensuring all 800 teaching staff and hundreds of teaching support staff had a consensus on what the trust considered great teaching, and how to deliver that, was the next big task - one achieved by creating its Teaching and Learning Ambassador programme in 2021.

ŌĆ£We went through the teaching standards and set out from a pedagogical perspective what it [great teaching] would look like in each of those areas,ŌĆØ says Wilkes.

To do this, the central team trained two or three ambassadors from each school, who in turn would then go out and train colleagues.

This, Wilkes says, helped create a ŌĆ£common languageŌĆØ across the trust whereby the ambassadors ensured everyone was on the same page on everything from group teaching and how to introduce new topics, to memory recall or fluency.

ŌĆ£We had to make sure every single person all the way through the trust was using the same language, not just a reading lead or a writing lead,ŌĆØ adds Wilkes.

4. No standardised curriculum or tests

Despite a standardised approach to teacher training, HET does not use a standard curriculum.

ŌĆ£We donŌĆÖt believe in that - weŌĆÖre a trust that gives really strong autonomy to our schools,ŌĆØ says Wilkes, noting, for example, that schools can choose their own reading, writing or phonics schemes (as long as it is government approved).

This approach also means its Teaching and Learning Ambassador role has evolved not to simply enforce curriculum delivery but to help teachers hone their craft.

ŌĆ£It more akin to responsive coaching, perhaps saying ŌĆśyou need to hone your craft in the automaticity or recall and respondŌĆÖ, so we are offering a form of bespoke mentoring.ŌĆØ

The trust also does not require schools to do tests to track progress: ŌĆ£I know a lot of trusts do testing but we donŌĆÖt do that,ŌĆØ says Wilkes. Instead, the expectation is for schools to be clear on pupil progress based on their curriculum: ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs the assessment - have they learned what youŌĆÖve taught them?ŌĆØ.

She acknowledges schools may still do practice tests themselves, or even as groups within the trust - but this is entirely their choice.

5. Data sharing

Another area of focus she attributes to the success in closing the disadvantage gap has been around sharing and interrogating data between schools.

ŌĆ£Every bit of data we collect, we see it as a central team, but we reflect all of that back to the schools, too - phonics data, reading data, attendance and so forth.ŌĆØ She says this means headteachers ŌĆ£spend a lot of time in each otherŌĆÖs schoolsŌĆØ to understand the successes they are achieving.

ŌĆ£They might say, ŌĆśtheir attendance is five per cent higher than oursŌĆÖ, and go and find out why, or ŌĆśthey have more pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) but their phonics score is higher and we use the same schemeŌĆÖ so they visit and realise theyŌĆÖre a bit tighter on a certain area and so on.ŌĆØ

She says this ŌĆ£professional curiosityŌĆØ is key - but can only be allowed to exist where data is not seen as something ŌĆ£secretiveŌĆØ but helps drive improvements.

6. Attendance push

Focusing on attendance to ensure all pupils are in school and able to learn has been another key focus, directed by the trust central team.

ŌĆ£We do school improvement visits purely based on attendance - we go and look at individual children and the systems around them and will support with parent meetings if theyŌĆÖre really complex,ŌĆØ Wilkes says.

There has also been a big push to make sure there is a view that ŌĆ£attendance is everyoneŌĆÖs responsibilityŌĆØ, with headteachers expected to be involved in this work.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs not just about your attendance person making a call and thatŌĆÖs it. You need to be checking in on pupils, finding out if thereŌĆÖs a concern, and using systems to support parents.ŌĆØ

Since doing this, attendance has risen from 93.5 per cent in 2021-22 (at 0.2 per cent below the national average that year) to 95.7 per cent in 2024-25 (now at 0.9 per cent above the national average).

Wilkes says this has ŌĆ£undoubtedly had an impact on outcomes for disadvantaged pupilsŌĆØ.

7. SEND training

Training on special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) has also been integral to ensure all teachers have the skills to support all pupils - something Wilkes says was based on the TeachersŌĆÖ Standards, too.

ŌĆ£Managing and supporting children with SEND is a key aspect of the TeachersŌĆÖ Standards - so the idea that SEND needs a completely different skill set I think is nonsense.ŌĆØ

To this end, the trust has leaned on the expertise in its special schools to train all staff in this area - not just Sendcos: ŌĆ£That knowledge should not be held on just one person - we run inset and training sessions for every single member of staff across the trust and will pay teaching assistants to come to those sessions, too,ŌĆØ she says.

ŌĆ£Everybody needs that same knowledge, because every interaction you have with a child is learning, so they need to know how to support them - if they have cognitive delay you need to know how best to cater for children with cognitive delay and so on.ŌĆØ

8. Accept itŌĆÖs not a linear path

Finally, while a headline figure of 75 per cent of disadvantaged pupils surpassing the national average for combined outcomes at key stage 2 is positive, to suggest the journey has been a clear linear path would be wrong.

ŌĆ£You often get a spiky profile,ŌĆØ admits Wilkes, who says getting all pupils to reach the expected standard in reading, writing and maths can be tough: ŌĆ£You might get two out of three, but all three is harder.ŌĆØ

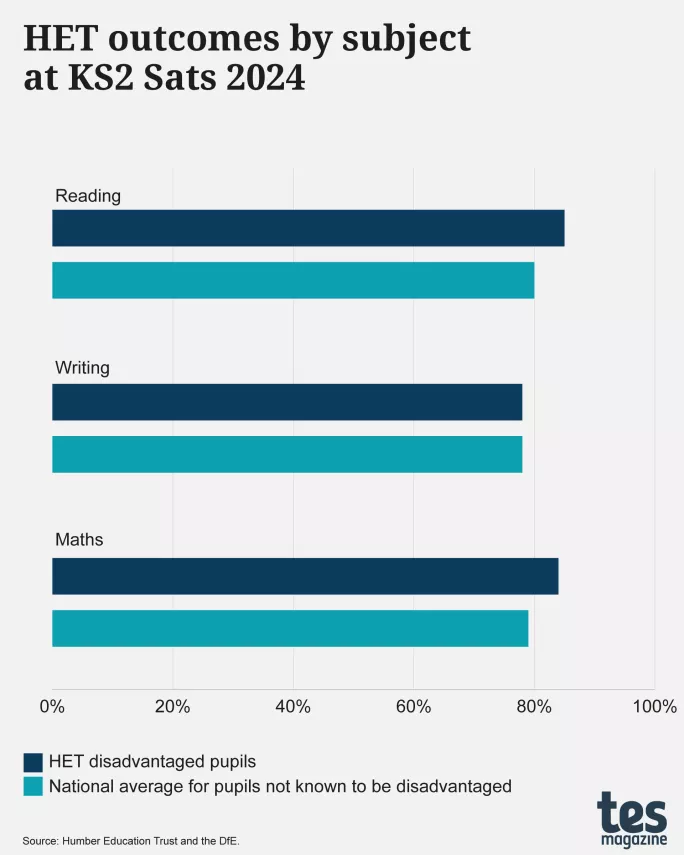

To that point, HET data shows while reading was six per cent above the national average for non-disadvantaged pupils and maths was five per cent higher, writing outcomes matched the national average at 78 per cent - a good outcome but not as high as the others.

╠²

Similarly, of its 13 schools that sit the Sats, two did not close the disadvantage gap this year but were narrower than the national disadvantage gap, something Wilkes says the trust knows is due to the writing score of pupils with EAL being slightly down.

As a result of these fluctuations, Wilkes admits she canŌĆÖt ŌĆ£guaranteeŌĆØ results will always close the gap - but the progress made so far shows it can be done.

ŌĆ£ThatŌĆÖs why teaching is so rewarding and exhausting, thereŌĆÖs never a point where you say brilliant job done - thereŌĆÖs always more you can do.ŌĆØ

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article