Watch any property programme on TV featuring a family in a large city and you can guarantee that at some point someone will say theyŌĆÖre looking for ŌĆ£a village feelŌĆØ.

Chances are the description of that village feel they are after means pubs, handy shops and a decent set of local schools to choose from - something they probably have no idea is entirely unrealistic and may make them rethink their countryside escape.

For example, if you live in Rochester in Kent, you can find exactly 50 primary schools within a three-mile radius. Certainly plenty to choose from, but far fewer than the 100 available in the same area around Rochester Way in South East London.

By contrast, if you live in the village of Rochester in Northumberland, your choice drops to exactly zero.

ThatŌĆÖs right. Schools are so sparse in some areas, that a search of the Department for EducationŌĆÖs Get Information about Schools database will tell you that no schools can be found.

A land of extremes

Clearly, the three-mile default radius is much less useful in rural areas. Of course, a school is available to those in Rochester, Northumberland - itŌĆÖs about 3.5 miles away and has 14 pupils.

(How you are meant to find this, though, when you canŌĆÖt change the radius parameter until after youŌĆÖve done a search is beyond me)

ThatŌĆÖs nothing, though, compared to the 33-mile drive to the allocated secondary school. Haydon Bridge High School near Hexham that stretches some 50 miles from the Scottish borders down to County Durham.

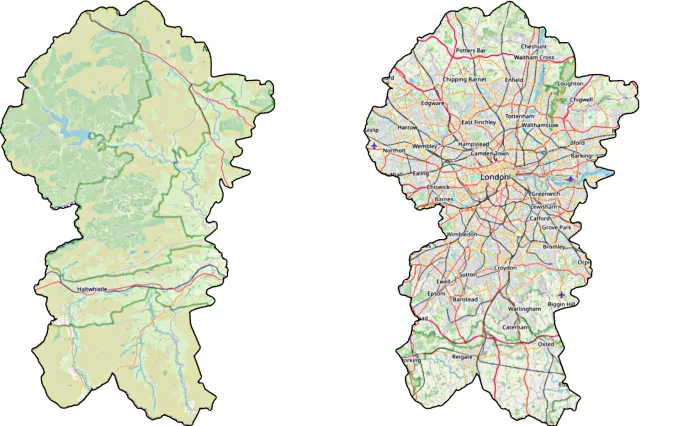

Its total catchment area is over 600 square miles - ever so slightly larger than the entirety of Greater London. By contrast, the capital has over 500 secondary schools in that area.

Catchment comparison: The image on the left is the catchment area for a single secondary school in Northumberland across 600 square miles. The image on the right shows the same catchment area overlaid on London, where there are over 500 secondary schools.

ItŌĆÖs tempting to dismiss this as a frivolity: after all, what matters is how many pupils there are to fill the spaces. But we know in truth that itŌĆÖs not as simple as that.

Dealing with attendance matters is a very different experience when most of your pupils live within a 10-minute walk of the school; not so when most of your school arrives by bus each day - and thatŌĆÖs before you think about the practicalities of after-school clubs or detentions.

Retention and recruitment are also a lot harder when staff face long commutes - almost entirely reliant on a car - and living a long way from anywhere, too.

The rural connection challenge

Such issues are not solely seen in rural settings and no doubt London schools face higher costs in some areas, which might justify an impact on funding levels.

Then again, the pleasant surroundings of the rural countryside are no substitute for easy access to museums, theatres or even public transport that might be available in the big cities.

Maybe the element of ŌĆ£competitionŌĆØ in urban areas can feel like an additional challenge at times, but schools can also benefit from proximity to local authority or trust neighbours that can share expertise, pool resources or even help sustain a wider group of teachers to recruit from.

At the same time, what choices for families? In the heart of a city, maybe the fear is that oversubscription means you might not get your first choice of secondary school; for huge swathes of the country, the idea of choice seems farcical when you only have one school within a reasonable distance.

Whether itŌĆÖs families, school leaders, teachers or pupils, the impact of rural sparsity makes a difference - and itŌĆÖs important that decision makers - in London and elsewhere - are mindful of that: what works in the big cities, wonŌĆÖt work everywhere. ItŌĆÖs a whole different world out there.

Michael Tidd is headteacher at East Preston Junior School in West Sussex

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter