MAT Tracker regional deep dive: West Midlands

The multi-academy trust system in the West Midlands is about to go through a period of transition as its regional director retires. Whoever takes over from Andrew Warren will oversee a region that ranks second in England for deprivation, and where GCSE students have, on average, been the in English and maths over the past six years.

They will also be overseeing a region where both secondary schools and primary schools are more likely to be academised, compared with the national average.

Each region in England has its own team to make decisions on academisation and trust growth, and - since the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA) started to move into the Department for Education in October - to provide financial oversight and support.

Tes has dived into the school and trust landscape in the West Midlands to reveal details about the decisions being made, the conversations happening behind the scenes and the likely direction of travel in the future.

Potential for academisation

There were 2,425 open state schools in the West Midlands in the 2023-24 academic year, according to the latest , which was released in June.

More than half - 54 per cent - are academies, placing the region fifth out of nine DfE regions for academisation.

Őż

Some 87 per cent of secondaries are academies, compared with an average of 80 per cent across England.

Meanwhile, 52 per cent of all primaries are still local authority-maintained, compared with 57 per cent across England.

As well as having 923 maintained primaries, the West Midlands has 56 nursery schools, 53 secondaries, 60 special schools and 23 pupil referral units run by local authorities (as of June).

This leaves most of the remaining scope for academisation in the primary sector - similar to the rest of England.

But academisation is not spread equally across the West Midlands. More recent data from November shows that Herefordshire still has 54 maintained schools - a figure exceeding its 42 academies.

Other local authority areas with more maintained schools than academies include Sandwell, Shropshire (though only by a few schools), Telford and Wrekin and Walsall.

In the rest of the local authority areas in the region, academies outnumber maintained schools. Only 10 maintained schools remain in Stoke-on-Trent and 28 in Solihull.

The MATs with the highest number of schools in the region include the Arthur Terry Learning Partnership (24 in the West Midlands), the Diocese of Coventry Multi Academy Trust (22), Staffordshire University Academies Trust (21) and the Shaw Education Trust (20).

CofE expects slower MAT growth

The growth in the number of academies in the region was already slowing before the change in government, figures show. Numbers increased by 19 per cent between 2015-16 and 2016-17, but by only 4 per cent between 2022-23 and 2023-24.

And Labour‚Äôs ‚Äúa≤Ķ≤‘ī«≤ű≥ŔĺĪ≥¶‚ÄĚ stance on trusts - combined with the removal of direct academy orders and changes to MAT funding - has left many in the sector with different priorities in terms of the way forward.

For some in the West Midlands, this means focusing on school collaboration rather than school structures, but others are still keen to get schools into MATs.

‚ÄúI think the reality now is the MATs we‚Äôve got won‚Äôt grow very fast at all,‚ÄĚ said the Reverend April Gold, director of education for the Diocese of Coventry, which oversees 76 schools across Coventry. Warwickshire and Solihull. Most of the maintained schools that the diocese looks after are rural schools in Warwickshire. Its academies are spread across six Church of England MATs.

‚ÄúThere would have to be a real meeting of minds on behalf of the trust and school if they wanted to join without any financial support, and that will slow things down,‚ÄĚ she added.

For the remaining small maintained schools, the Reverend Gold said joining a MAT does not always help without bigger schools also being in the mix. ‚ÄúCreating an economy of scale just isn‚Äôt the reality of the Church school estate in Coventry and Warwickshire,‚ÄĚ she added.

Catholic diocese creating one of the biggest MATs

On the other hand, in September 2025 the West Midlands will become home to one of the biggest MATs when six Catholic multi-academy companies (MACs) and seven voluntary-aided schools come together to form a 63-school trust.

Steve Bell, director of education for the Archdiocese of Birmingham, told Tes: ‚ÄúThere is a lot of strength in maintained schools but from my experience, and what I‚Äôve seen as a former MAT CEO, we are better together in a MAT structure.‚ÄĚ

He added that the archdiocese still plans for its 55 remaining voluntary aided schools to join MATs.

The third highest number of conversions

Regardless of Labour‚Äôs agnosticism, academies will continue to be a crucial part of the infrastructure, Mr Warren suggested at last month‚Äôs Schools and Academies Show. ‚ÄúThe majority of children in the West Midlands are in academy trusts. Academies have to play an important part and they will play an important part,‚ÄĚ he said.

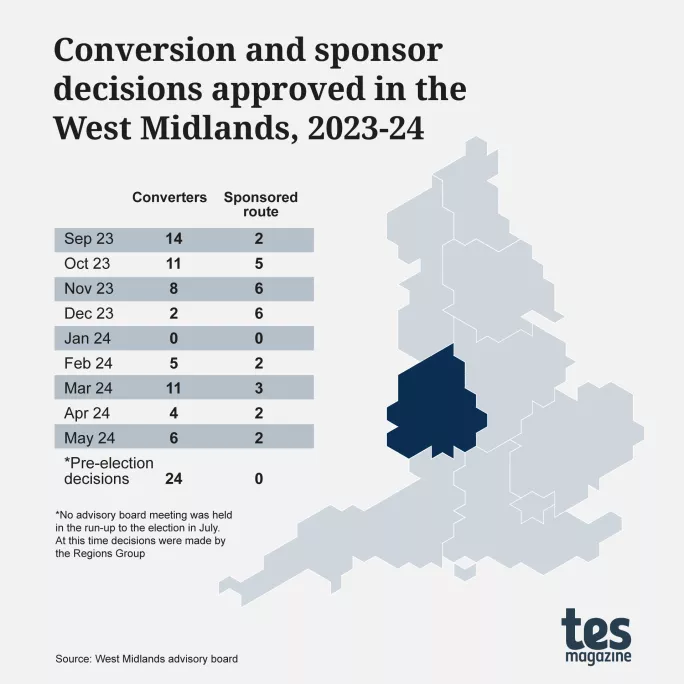

Mr Warren has been making decisions on academisation in the area for nearly six years and is due to retire in December. Tes analysis shows that the West Midlands was the third busiest region in terms of approving conversions from September 2023 through to April 2024.

Over 2023-24, there has been a steady stream of conversions (85) approved at the regional advisory board - though some of these (24) were approved during the pre-election period when meetings were not happening.

The board has also approved 28 schools joining MATs through the sponsored route, seven new MATs, 13 schools changing trusts and 12 single-academy trusts becoming MATs.

Őż

Speaking at the Schools and Academies Show about how he has made decisions on academisation, Mr Warren said: “I have to ask some fundamental questions, one of which is: why is this coming to me? Why is it a really good case? I need to judge givers and takers and what’s in it for both the school joining the trust and the trust taking them on.

‚ÄúHowever broken a school might be, there‚Äôs always something that school can contribute.‚ÄĚ

He added that he takes account of how the trust’s values fit in with the school community that it will be absorbing.

‚ÄúMy job is to make sure that the growth that happens is well-founded, well-reasoned and will provide impact for the kids in the short and medium term,‚ÄĚ he said.

He added that he has seen a lot of mergers coming to the advisory board. ‚ÄúI hope all schools are in strong families, because I think that works best,‚ÄĚ Mr Warren added.

In the West Midlands, he is seeing more of the larger trusts taking greater account of their local governing bodies, he said.

However, concerns have been raised about transparency of the regional system in the past.

One West Midlands CEO told Tes they would like to see more consistency in decision-making across the country.

‚ÄúI think we‚Äôre going through a period of transition at the moment, as Andrew Warren is retiring. But in terms of education, there‚Äôs a lot of change happening and this is the time where we need the most communication,‚ÄĚ the CEO added.

In October, when it was announced that Mr Warren would retire, the DfE said his replacement would be announced ‚Äúin due course‚ÄĚ.

Collaboration ‚Äėnot always forthcoming‚Äô

Bridget Phillipson, the education secretary, has said that the government wants to evolve the system to adopt a ‚Äúcollaborative model‚ÄĚ rather than a competitive one. Right now in the West Midlands, leaders report a mixed picture.

Andrew Morris, CEO of five-primary Severn Bridges Multi Academy Trust, in Shropshire, said there are opportunities for collaboration locally. He attends a CEO forum in Shropshire and has good links with the local authority for discussing gaps in provision and how they can work together to fill them.

He also chairs a ‚Äúlearning set‚ÄĚ of CEOs across the West Midlands, which he said allows him to visit other schools and discuss key issues with others in the region.

‚ÄúIt feels quite open in our region and progressive in that way,‚ÄĚ he explained.

However, Carla Whelan, CEO of Empower Multi-Academy Trust, which has eight primaries in Shropshire, said collaboration is ‚Äúnot always forthcoming‚ÄĚ.

‚ÄúSome trusts hold this in high regard and others are more internal. This has to develop for our education system to grow,‚ÄĚ she said.

A group of trust CEOs in the region have recently set up their own Education Exchange system, based on a model in Yorkshire. It will match schools with capacity and expertise in certain areas, such as special educational needs and disabilities or a particular curriculum area, with schools that request support.

Vince Green, CEO of Summit Learning Trust, which has nine schools across Birmingham and Solihull, said the region’s local authorities and the DfE regions team have supported the initiative.

‚ÄúThe regional director spoke about how the Education Exchange in the West Midlands will work alongside the new regional improvement teams. The teams won‚Äôt be able to do it on their own - by definition - and will need to tap into support,‚ÄĚ he said.

‚ÄúThe exchange will be there to help identify expertise.‚ÄĚ

The Reverend Gold said Coventry Diocese’s six MATs have always collaborated, but have also had to compete for schools.

‚ÄúNow that has been taken away, I feel I‚Äôm in a position to say, ‚ÄėLet‚Äôs get around the table,‚Äô and decide what capacity they‚Äôve all got and how best to use that,‚ÄĚ she said.

She added that the diocese has not seen much financial benefit in grouping small primaries into MATs: the value of joining trusts has been for collaboration.

The Archdiocese of Birmingham currently has 16 different MACs of various sizes across different areas, ‚Äúwhich does stifle the ability for them to work together as much as they could,‚ÄĚ said Mr Bell. ‚ÄúBut when the first six join the new MAT in September 2025, I think we will start to see true alignment.‚ÄĚ

‚ÄėMore recognition of deprivation‚Äô needed

Leaders in the region hope more collaboration in the system will help them to tackle issues that schools are facing across the country, such as rising demand for SEND support, and poverty.

After the North East, the West Midlands has the highest proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals (FSM) in England, at 28.9 per cent as of 2023-24.

The need for ‚Äúrecognition of how deprived some of our areas are‚ÄĚ - and how this should be factored into discussions about trust performance - is a key challenge in the West Midlands, says Lisa Sarikaya, CEO of St Bart‚Äôs Multi-Academy Trust, which has 23 schools across Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire and Cheshire East.

Birmingham drives this deprivation, as the second largest urban area in the country: 39.8 per cent of pupils (more than 80,000) there were eligible for FSM in 2023-24.

Walsall (33.7 per cent) and Sandwell (33.8 per cent) also have significantly above-average FSM.

Of the 14 local authorities in the West Midlands, five have FSM below the national average - Herefordshire, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. In general, these are the more rural areas.

Mr Green said improving academic outcomes is a ‚Äúbig priority‚ÄĚ for the region, as well as improving attendance.

‚ÄúDisadvantage in all forms is our greatest challenge,‚ÄĚ he added.

Key stage 4 performance data for 2023-24 shows that the average Progress 8 score in the West Midlands was -0.11, which was lower than the -0.03 across England.

This year the West Midlands saw the second lowest percentage of pupils achieving the grade 4s needed to pass English and maths (62.1 per cent).

On average between 2018-19 and 2023-24, only 65.2 per cent of students in the region met that standard - the lowest figure for all of the English regions.

Unregulated AP ‚Äėfilling gaps‚Äô

The previous government introduced education investment areas (EIAs) as a measure to tackle areas of lower performance. There are five in the West Midlands: Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Stoke-on-Trent and Walsall.

published in March 2023 set out priorities for academisation in each of these areas, and all of those in the West Midlands flagged a need for more special and alternative provision (AP).

‚ÄúSEND and AP challenges - that‚Äôs a massive issue here,‚ÄĚ said Mr Morris. ‚ÄúThere is a lot of unregulated AP filling gaps for us.‚ÄĚ

The Birmingham archdiocese hopes its MAT plans will address this.

‚ÄúWe‚Äôll be able to be more creative in terms of how we support children with SEND, because we can provide specialist provision,‚ÄĚ Mr Bell said. ‚ÄúWe‚Äôre not talking about more money. We‚Äôre talking about using existing money more effectively and working with other organisations, such as Olive Academies, to make that happen.‚ÄĚ

This all comes with the DfE’s new Regional Improvement for Standards and Excellence (RISE) teams set to start supporting a few schools from next year.

“School improvement can be so fragmented, so it would be great if they can tie it all together and make a more logical system, said Mr Morris.

‚ÄúThere‚Äôs a real mix of support here, and if they bring that together I think that will be key.‚ÄĚ

Find our interactive map of England’s multi-academy trusts by clicking here, where you will also find links to all of our MAT Tracker content

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article