Will the teacher pay ŌĆśfarceŌĆÖ continue under Labour?

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs that time of year - itŌĆÖs the waiting game,ŌĆØ says Jack Worth, education economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER).

Worth is referring to the upcoming announcement on teacher pay, as the elongated process for deciding the 2025-26 awards drags on.

Since 1991 the School TeachersŌĆÖ Review Body (STRB) - an independent panel appointed by the education secretary - has consulted with sector organisations, including unions and local authorities, to make recommendations to the government on teacher pay.

The government doesnŌĆÖt have to follow these recommendations, and, in fact, submits its own evidence to the STRB in the form of either a specific percentage increase or a more general comment about what is and isnŌĆÖt affordable.

After the STRBŌĆÖs report is published there is then a nerve-racking period during which schools wait to hear whether the government will agree with the panelŌĆÖs recommendation - and, crucially, whether it will fund any pay award.

This year the process has already been going on for some time. It was in December that the government proposed a 2.8 per cent pay increase for 2025-26. The STRB report is yet to be published but, according to details leaked last month, the body advises an uplift of almost 4 per cent.

What the government will decide remains to be seen, with experts expecting that the final decision will come as part of the Spending Review, due to conclude on 11 June.

Teacher pay and school budgets

If this sounds late in the day for schools needing to plan their budgets for September, itŌĆÖs actually earlier than usual - a ŌĆ£unique aspect of this yearŌĆØ, says Worth. In recent years decisions havenŌĆÖt been made until July - sometimes after schools have broken up for the summer, and always far later than is helpful for budget planning.

ŌĆ£The historical norm is a bit of a farce,ŌĆØ says Luke Sibieta, research fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. He suggests a better system would be for ŌĆ£the recommendations to be made early and for government to then make it clear how much itŌĆÖs asking schools to pay and how much itŌĆÖs providingŌĆØ.

Sibieta adds that the Labour government tried to do that by starting the STRB process earlier than usual. In September education secretary Bridget Phillipson outlined her plans to ŌĆ£announce the upcoming pay awards as close to the start of the financial year of 1 April as possibleŌĆØ. But that hasnŌĆÖt quite worked out.

The historical norm

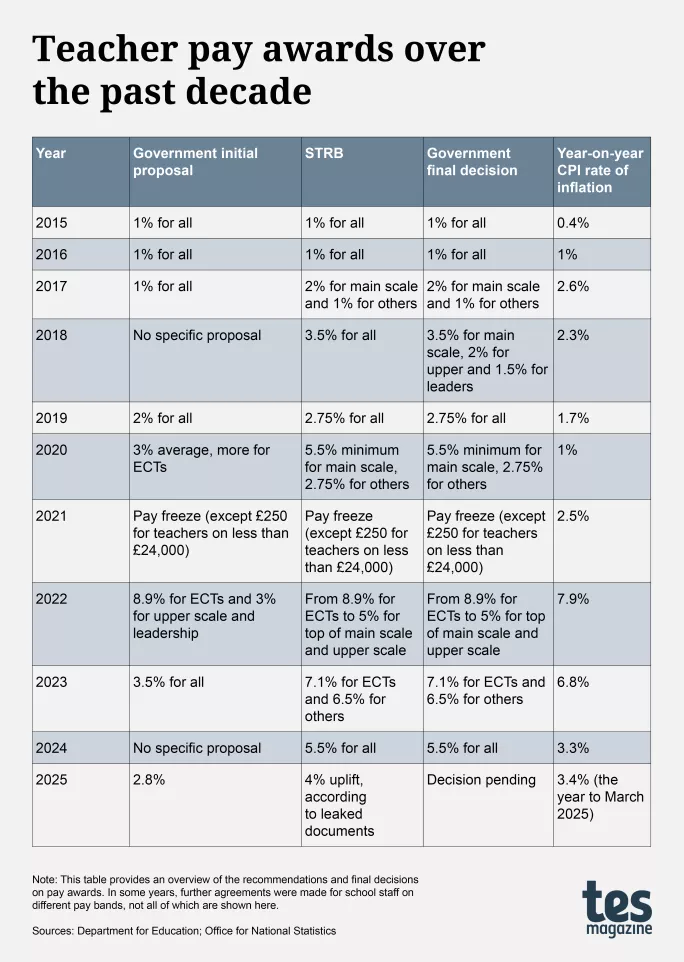

As we wait, letŌĆÖs look back at how the teacher pay review process has worked out over the past decade.

The table below shows the governmentŌĆÖs proposed teacher pay rises for each year since 2015, what the STRB recommended and what the governmentŌĆÖs final decision was. It also shows how these figures compared with the consumer price index rate of inflation at the time.

As you can see, there is a precedent for the government to accept the STRBŌĆÖs recommendations.

The exception came in 2018, when the government only accepted the STRBŌĆÖs recommended 3.5 per cent for teachers on the main scale, awarding 2 per cent for those on the upper scale and 1.5 per cent for school leaders.

This year there is a discrepancy between the governmentŌĆÖs proposed 2.8 per cent rise and the rumoured STRB recommendation of 4 per cent. But that doesnŌĆÖt mean a final decision of 4 per cent is unlikely. In fact, the data from the majority of the past decade - including as recently as 2022 and 2023 - shows that the government often concedes to the STRB even when there is an initial gap between recommendations.

This year ŌĆ£is very much following the historical normŌĆØ, says Sibieta, who explains that ŌĆ£what normally happens is the government recommends something, the pay review body either says itŌĆÖs about right or needs to be a bit higher, and, in the end, the government provides the moneyŌĆØ.

Teacher retention versus affordability

However, Worth points out that ŌĆ£thereŌĆÖs also precedent for government taking a different line to what the STRB has recommendedŌĆØ - as in 2018. So ŌĆ£until the government says what its response will be, we donŌĆÖt know what its response will beŌĆØ.

Worth says that the final decision will be hugely important for a sector with a teacher retention and recruitment crisis. NFER research found that the governmentŌĆÖs plan to recruit 6,500 new teachers would require pay rises of nearly 10 per cent for two consecutive years.

But, in making its recommendation, the STRB has to ŌĆ£trade offŌĆØ recruitment and retention difficulties with affordability, Worth explains. ŌĆ£These things are often in tension,ŌĆØ he says.

For schools, the main concern is not just the size of the pay award but to what extent it will be funded.

ŌĆśEfficiencyŌĆÖ savings

In the analysis that the government published alongside its 2.8 per cent recommendation, it admitted that schools would have to find ŌĆ£efficienciesŌĆØ to afford the uplift - leading some to fear that it will not offer a grant.

Talk of schools finding ŌĆ£efficienciesŌĆØ is a ŌĆ£fantasyŌĆØ, according to Pepe DiŌĆÖIasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders. ŌĆ£The truth is that every budget line was cut to the bone and beyond long ago, and ŌĆśefficienciesŌĆÖ simply means more cuts.ŌĆØ

Looking at the numbers, Sibieta estimates that without a grant ŌĆ£schools can probably afford around 1.5 to 2 per cent, so [nationally] the Department for Education are effectively asking schools to make efficiency savings of around ┬Ż500 million in order to afford the pay riseŌĆØ.

Of course, even more savings will be needed if the STRBŌĆÖs reported 4 per cent for teachers (as well as 3.2 per cent for support staff) is approved, he adds. ŌĆ£That would probably cost schools ┬Ż800 million more than they have.ŌĆØ

Funding difficulties

This is a worry for Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the NAHT school leadersŌĆÖ union. Referring to the real-terms drop in teacher pay over recent years, with pay rises failing to keep pace with inflation, he says school staff ŌĆ£absolutely deserve a pay award that moves them closer to full pay restoration, but that needs to be fully funded - most schools simply do not have the headroom within their existing budgetsŌĆØ.

However, Worth points out that the government could still fund a pay award. ŌĆ£ThereŌĆÖs plenty of precedent for a teacher pay grant to cover that additional cost,ŌĆØ he says.

What exactly has happened in recent years with funding for pay rises is not clear cut. Looking historically, Sibieta says ŌĆ£it is effectively impossibleŌĆØ to say whether each yearŌĆÖs pay award has been fully funded or not because for each year it depends on ŌĆ£whatŌĆÖs happening in the [school funding] baseline and therefore what the extra is relative toŌĆØ.

An exception came in 2024 when the government fully funded the pay award by providing ┬Ż1.2 billion via the new core schools budget grant.

In other years the government may not have given schools a pay grant but an increase in school funding might still have covered the additional costs.

So while the government has usually funded the rise, a difference in approach means ŌĆ£thatŌĆÖs always been quite non-transparentŌĆØ, Sibieta adds.

The problem with averages

What makes the situation more challenging for schools is that the government calculates funding using averages. But what is an ŌĆ£averageŌĆØ school? A small, maintained primary runs on a very different budget to a secondary thatŌĆÖs part of a large multi-academy trust.

This is also part of the issue for Whiteman, who says: ŌĆ£The government also needs to be aware that working out school costs on an ŌĆśaverageŌĆÖ basis does not tell the full story, and we know there are specific types of school that face particularly acute cost pressures.ŌĆØ

On a systems level, Sibieta thinks the averaging process is nonetheless ŌĆ£the only practical solutionŌĆØ. ŌĆ£I think the averaging is still useful, because all schools will feel a similar picture, although the costs differ,ŌĆØ he says.

Worth agrees: ŌĆ£It boils down to the principle that governments, over many years, have taken the decision to provide the funding on a per-pupil basis, and itŌĆÖs up to schools to manage the rest.ŌĆØ

If the government was to get involved in funding at an individual school level, ŌĆ£it would get immensely complicatedŌĆØ, he adds.

Teacher recruitment pressure

For the time being, schools must wait to find out what the teacher pay award will mean for next yearŌĆÖs budgets.

There is unlikely to be any overhaul of this complicated process soon - as even the attempt to bring it earlier in the calendar has failed, leaving schools in a more precarious position with every passing day, as Worth explains.

ŌĆ£One of the major difficulties is the recruitment window for next year is now, so schools are making decisions based on what they think theyŌĆÖll have available, which may or may not be influenced by the pay review decision.ŌĆØ

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

YouŌĆÖve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article